Soldiers, Sailors, and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force!

You are about to embark on a Great Crusade toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hope and prayers of liberty loving people everywhere march with you…

Your task will not be an easy one. Your enemy is well trained, well equipped and battle hardened. He will fight savagely….

But this is the year 1944! …The tide has turned! The free men of the world are marching together to victory.

I have full confidence in your courage, devotion to duty, and skill in battle. We will accept nothing less than full Victory!

Good luck! And lets all beseech the blessing of Almighty God upon this great and noble undertaking. ꟷ General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, June 6, 1944.

Each year on 6 June, the world honors the memory of the Allied troops who stormed the beaches of Normandy, France. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the World War II invasion, known as D-Day, that led to the liberation of Europe and the defeat of Nazism.

Background

In 1938, the German Army proceeded to occupy the countries of Western Europe. Beginning with the Rhineland (Western Germany), Adolf Hitler subsequently took over Austria and Czechoslovakia with little opposition. His invasion and conquering of Poland in 1939 led Britain and France to declare war. Efforts to stop Hitler failed, and his massive forces moved through Europe. By the summer of 1940, most citizens in western Europe were living under Nazi control… Britain was next. On 10 July 1940, the Battle of Britain began. More than 15,000 tons of bombs fell, but under the leadership of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the Germans could not break the resolve of the British people. With this failure, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. On 7 December 1941, the Japanese attacked the American military base at Pearl Harbor, leading to a United States declaration of War against Japan, and three days later Germany declared war against the United States. Americans mobilized quickly, building military equipment and expanding their armed forces. Massive amounts of weapons, supplies and personnel were sent to England as one important component of preparing for an eventual Allied invasion to regain control of Europe. On 7 December 1943, two years after the Japanese Pearl Harbor attack, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt named General Dwight D. Eisenhower as Supreme Commander of the Allied forces. Other countries, including Canada, joined the alliance. The challenge was great ꟷ the consequences of failure would be horrible.

The nature, site and date of the invasion were carefully determined. By the spring of 1944, all aspects for Operation Overlord, the invasion of France, were ready. Secrecy was paramount. It was a risky undertaking. German defenses in France were strengthened in preparation of an expected Allied attack. Concrete-reinforced steel pillboxes, barbed wire, mines, artillery, machine gun nests, mortar pits, and beach obstacles were constructed. Originally scheduled for 5 June, inclement weather forced a postponement of the invasion. Allied meteorologists predicted a small and last best window of opportunity on June 6th. General Eisenhower gave the order for battle. The invasion began at 06:30 am. The first official news came at 9:30 am, when the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force issued the bulletin, “Under the Command of General Eisenhower, allied naval forces supported by strong air forces, began landing Allied Armies this morning on the Northern Coast of France.” In preparation for the landing, more than 2,000 Allied aircraft conducted pre-dawn bombing raids along the beaches. An estimated 200,000 Allied forces participated in the landing force — the largest invasion by sea in the history of the world — at five landing beaches along the coast of Normandy. They were wet, cold, seasick, and determined. Many were killed the instant they waded into the chest-high water. There was a tremendous loss of life. With courage, the D-Day objective, defeating the first line of German defenses was accomplished. After five days, more than 326,000 troops, 54,000 vehicles and 104,000 tons of supplies hand landed. The battle of Normandy (D-Day) ended, but the war continued for almost another year. Allied forces advanced north, liberating the Netherlands in April. Nazi Germany’s defeat was now imminent. German forces in Italy surrendered on 2 May. Those in northwest Europe surrendered five days later. Almost six years after it had begun, the war in Europe was over.

British Admiral Sir Bertran Ramsey stated one week before the invasion “It is a tragic situation that this is a scene of a stage set for terrible human sacrifice, but if out of it comes peace and happiness, who would have it otherwise?” At an enormous cost of lives, D-Day did bring victory with peace. Many of those who died on the beaches and in the following bridgehead battles are buried in war cemeteries near the site of invasion.

We honor the many heroic men and women who lost their lives. We honor the many who returned home physically and mentally injured. We must recognize and never forget this necessary action that provided citizens of the world and their descendants the opportunity to develop and prosper in freedom.

D-Day Management, Science, Engineering, and Technology

D-Day, the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II, involved the best of existing — and in many cases newly created — special purpose Allied innovative science, engineering and technology. The creation and application of these technologies were all carefully planned, tested and managed to maximize their strategic value to the Allies. These special purpose Allied solutions, combined with leadership acumen, meticulous planning, deception, the resistance of European citizens, and the bravery of soldiers, contributed to the success of the D-Day landings and the eventual liberation of Europe. Here are some of the most remarkable strategies:

Surveying the Beaches and Countryside

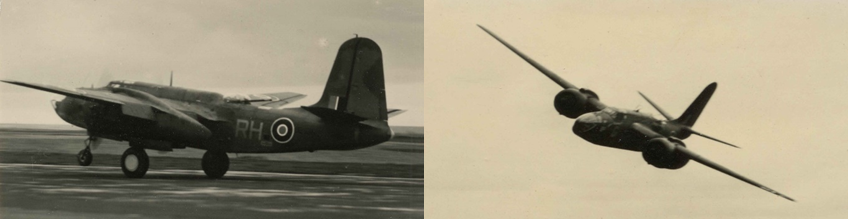

High-altitude Spitfire aircraft photoreconnaissance of the beaches was conducted in advance using a F52 camera equipped with a 36-inch lens. This provided the high-contrast gradient information used to map and select the best landing sites. Other photoreconnaissance revealed details of the countryside, including German defenses, inland railway, road, airfield, bridge, and radar bombing targets.

Weather and Tide-Prediction

Success of the D-Day invasion was dependent upon weather conditions, the position of the moon, and the tide. The weather in the English Channel is difficult to predict. Air forces required clear skies and a full moon for good visibility. Naval forces required calm seas. Ground troops needed a low tide so they could exit their landing craft and deactivate beach obstacles. It was not easily known when a full moon would coincide with low tide at the desired time of invasion. The Army consulted numerous meteorological experts, including the British mathematician Arthur Doodson, who created a machine that could predict future tidal patterns. This provided the Supreme Allied Commanders with the best date and time for the D-Day landings.

Code-Breaking

Intelligence was a critical factor in the Allied victory. The Allies used various methods and sources of intelligence to gather information, deceive the enemy, and coordinate the operation. They were able to decrypt many of the German messages that were encoded by the German Enigma machine, a complex device that used rotors and wires to scramble the letters. This machine was considered so secure that it was used to encipher the most secret German messages. Code-breakers at Bletchley Park, a secret facility in England, used mathematical techniques and machines to crack the code and read German communications. This gave the Allies valuable insights into German plans, movements, strengths, and weaknesses.

The French Resistance

The Allies also relied on the help of the French Resistance, a network of underground fighters who opposed the Nazi occupation. The Resistance provided the Allies with important intelligence on the German defenses, sabotaged the German infrastructure, and assisted the Allied troops after their landing. The Resistance also coordinated with the British Special Operations Executive, a secret organization that sent agents, weapons and supplies to support the Resistance. They engaged in covert actions, such as assassinations, raids and propaganda, to undermine German morale and authority.

Deception

The Germans knew that the allies would launch a cross-Channel invasion, but were unaware of exactly where or when it would take place. As a crucial part of their preparations for D-Day, the Allies developed a deception plan to draw attention away from Normandy. They misled the Germans about the time, place and scale of the invasion. They created a fictitious army group, called the First US Army Group, and placed it near Dover, England, the closest point to France, across the English Channel. They gave the impression that the invasion force was larger than it actually was using inflatable Sherman tanks, dummy planes, fake radio traffic, and double agents. The most famous of these agents, Juan Pujol Garcia (‘Garbo’), invented a network of imaginary agents. These deception operations, collectively known as Operation Fortitude, succeeded in diverting the German attention and resources away from Normandy, where the invasion was actually going to occur. The Allied deception strategy for D-Day was one of the most successful ever conceived.

Pre-Invasion Preparation

In the months leading up to D-Day, Allied bombers attacked road and rail networks in an attempt to isolate the invasion area. Additional attacks were made on other parts of northern France as a deception to divert German attention away from Normandy. This helped the Allies achieve an element of surprise and prohibited German reinforcements from reaching Normandy both on D-Day and in the following weeks. The Royal Air Force dropped metal strips along the French coast to confuse German radar. On the night of 5-6 June, they also dropped dummy parachutists to simulate an airborne invasion away from the Normandy beaches.

Landing Boats

An earlier failed raid at Dieppe in August 1942 exposed how difficult it was to land armored vehicles during an amphibious invasion. Thousands of mission-designed landing craft were constructed in England. These were used to transport men, vehicles, equipment, and supplies across the Channel. The use of specialized landing craft ensured that the Allies could land troops and heavy equipment, such as tanks, on strongly defended beaches. This was a solution to the difficult problem of immediately securing existing harbors and ports which were strongly defended by the Germans.

Horsa Gliders

Thousands of gliders, constructed of wood and fabric, were towed by powered aircraft and released over their target drop zone. They glided to their landing zones, where equipment, weapons, ammunition, and other supplies were deployed. Gliders also transported heavy equipment that could not be delivered by parachute. Their hinged nose and removable tail section allowed cargo to be unloaded easily. These gliders made significant contributions throughout WW II.

Specialized Armored Vehicles

Special vehicles that could perform essential tasks were designed and manufactured in secret. Armored bulldozers were used to clear debris, remove obstacles on the beaches, and level areas needed by the military. The Sherman Duplex Drive tank was designed with skirted inflatables for flotation and an aquatic propulsion system to advance to the beaches. The carpet layer tank could lay reinforced matting on the sand to support allied vehicles. The Crab tank was designed to destroy the effectiveness of German minefields. The Beach Armored Recovery Vehicle assisted vehicles that had become disabled by rollover or malfunction. The Rhino tanks were fitted with prongs on the front which cut through the countryside bocage. The Assault Vehicle had a large mortar that could propel massive explosive charges. British Crocodile tanks were fitted with flamethrowers that could emit a flame and were used to attack pillboxes and bunkers. With the creation of these specialized armored vehicles Allied leaders ensured troops had every opportunity for success.

Mulberry Harbors

After the D-Day invasion, the Allies needed a way to move reinforcements of men and supplies to Europe. As a solution, it was proposed to create two artificial harbors — codenamed ‘Mulberries.’ The base was formed by large concrete structures. The addition of a floating roadway and piers would allow the use of these structures as an improvised port, facilitating the rapid unloading of troops, vehicles and supplies, bypassing heavily German defended ports.

Pipeline Under the Ocean (PLUTO)

PLUTO supplied gasoline from Britain to Europe through an underwater network of flexible pipes. The 3” pipeline wound around giant spools was deployed across the Channel. This gave the Allied forces access to fuel for their aircraft and vehicles. Two PLUTO pipelines ran from the Isle of Wight to the linkup point between Omaha and Gold beaches. Another pipeline was added later, running from the Kent coast to Boulogne France. The network was expanded as the Allies advanced across Europe, ensuring a steady flow of fuel during the war.

Women and WW II

In Great Britain, Australia, Canada, and the Soviet Union, women worked on the home front. Millions of women worked in factories, others volunteered for the Red Cross, and over 200,000 served in non-combatant roles in the military. The vital role of women during Second World War (msn.com). Women served as cryptographers (code makers) and cryptanalysts (code breakers). Women were trained in small arms ammunition production, electrical repairs, quality control inspectors, welders, riveters (affectionately known as Rosie the Riveter). These real-life ‘Rosie the Riveters’ just received the top U.S. civilian award | CBC Radio. Women also worked as Special Operations Executive agents and with the French resistance behind enemy lines.

Animals and D-Day

Animals participated in D-Day, either as part of the Allied forces or as local helpers. The first soldiers on Normandy soil on D-Day were parachutists who landed in various locations just after midnight, and among them there were also dogs. These “paradogs” were trained to detect mines and act as an early warning system for approaching enemy soldiers. Homing pigeons were used to send messages back to Britain. Horses were used by the troops after the invasion to move quickly or to transport supplies. Some horses pulled carts loaded with equipment through enemy fire. Some soldiers adopted cows as mascots and gave them names.

Leadership and D-Day

D-Day was a complex and critical operation that required courageous leadership, decision-making, and problem-solving, as well as advance planning and continuous adjustment to meet unforeseen and changing conditions. Many men and women played important roles in the planning and execution of the campaign.

Allied Leadership:

General Dwight Eisenhower: Eisenhower was the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Forces. The original date chosen for D-Day had to be changed because the weather forecast was unfavorable. Eisenhower agreed to postpone the invasion one day, despite the logistical difficulties and risks of delaying the operation. The weather was still not ideal. General Eisenhower made the decision to invade and was prepared to accept the full responsibility should the invasion fail. His letter should the invasion not be successful stated “Our landings…have failed and I have withdrawn the troops. My decision to attack at this time and place was based on the best information available. The troops, the air and Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.” Fortunately to the benefit of humanity, the logistically difficult invasion did not fail.

D-Day success was the result of considerable leadership acumen. Timeless, valuable lessons applicable to anyone in a position of leadership emerge. A leader has a lifelong understanding of duty, championing the cause with persistence and with clear direction while tempering the path with adaptability to change when necessary, and respecting the opinions of others. A leader is inspirational, optimistic, honest, trustful, and humble ꟷ willing to subjugate their own ego. A leader recognizes and deals effectively and quickly with harmful behavior. A leader understands the recognizes and the possibility of unrecognized costs of their actions. A leader ensures that all stakeholders understand the “why” of the cause, and establishes metrics of success. Finally, a leader is self-confident and has a sense of humor resulting in the affection, loyalty and admiration of all.

There were numerous strategic leadership decisions critical to success made by Eisenhower and his Supreme Allied Command team that embody the crux of leadership. A selection of some of these include:

- Meticulous advance planning (due diligence) prior to the invasion facilitated identification of Allied and Axis strengths and weaknesses. Allied leadership built strength and mitigated weaknesses with creative thinking and innovative engineering. Eisenhower himself made many motivational visits to the troops in the months before D-Day. He often stated, “I belonged with the troops….with them I was always happy.” He wanted them to see their commander.

- The Allies understood the strategic value of surprise and deception, particularly the choice the Normandy Beaches. This was the longest, and hence, the most unexpected route across the English Channel.

- The Allies understood the importance of destroying Normandy’s inland infrastructure so that Germany could not easily move forces to the coastline. Eisenhower himself made frequent trips to the battlefront ensuring that he had firsthand “unfiltered” knowledge of the conditions the troops were fighting under.

- The Allies planned beyond D-Day, determining what would be necessary after a successful invasion to re-capture occupied countries and establish peace throughout Europe. Importantly, this included historical recognition of the sacrifices of those who fought for freedom.

General Eisenhower had a skilled team of international military leaders who were members of the Supreme Command to advise him:

- General Omar Bradley was the commander of the First U.S. Army Group. He led the American forces that landed on Omaha and Utah beaches and later advanced into France and Germany.

- Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery was the Commander in Chief of the Allied Ground Forces, which consisted of the British Second and Canadian First Armies. He planned and executed the landings on Gold, Juno, and Sword beaches, and later led the Allied forces in the Battle of Normandy and the liberation of northwest Europe.

- Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder was the Deputy Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force and the chief of the Allied air forces. He oversaw the air strategy and operations for the invasion and the subsequent bombing campaigns in support of the ground forces.

- Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay was the Naval Commander of the Allied forces. He organized and supervised the naval aspects of the invasion, including the transportation, landing and protection of the troops and supplies.

General Eisenhower also consulted with Allied government leaders, particularly Winston Churchill (Britain), Joseph Stalin (Russia), and Franklin Roosevelt (United States). These three government leaders facilitated the strategies determined by the military leaders, ensuring that their countries’ economic, manufacturing, and human resources were available to enable the D-Day plan.

According to Professor Keith Grint, a researcher who studied D-Day, there are three types of problems that leaders face: wicked, tame and critical. Grint argues that the Allies succeeded on D-Day because they had a balanced and holistic approach to these problems. The Allies had an internationally diversified and collaborative team of leaders, who each contributed their expertise and perspective as members of the Supreme Command to the entire operation. The leadership philosophy of D-Day required leaders to understand the nature and complexity of the problems they faced, and have the skill and flexibility to adopt the appropriate style of leadership, decision-making, and problem-solving required for each situation. They also worked effectively with people from many nations leveraging their collective strengths and resources. They engaged in open communication with all, encouraging and respecting their contributions. Finally, they were flexible and adaptable to changing circumstances and challenges.

Axis Leadership

Adolf Hitler: The German leadership was a striking contrast to that of the Allies. Hitler was the Führer (leader) of Nazi Germany and the supreme commander of the German armed forces, a task-oriented, instinctively driven ruler by decree and believer in racial supremacy. Hitler’s charisma, cult of personality, determination, tenacity, intelligence, and promises of a strong German economy/jobs were sources of power. He used a powerful oratory and propaganda to manipulate his audience. He controlled selective access to information, brainwashing the public and indoctrinating youth education. He led autocratically, insisting on absolute obedience through fear and intimidation. He believed that victories were because of him and not his generals. He interfered with his generals’ decisions and personally controlled all decisions concerning strategy, the war’s timing, targets, and goals, making strategic blunders that contributed to the failure of the German defense of Normandy. He was stubborn, distrusted his generals and monitored everything in detail. He encouraged distrust, competition and infighting among his subordinates, using fear and intimidation to maximize his own power. The Germans failed because they focused too much on their strength in combat. He assumed an easy victory and had no back-up plan. The centralized and rigid command structure made costly mistakes. It was his personality, focus on his own selfish goals, and unchecked authority that inevitably led to Germany’s defeat.

Hitler’s military advisers had limited authority to advise or take action. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was in charge of fortifying the Atlantic Wall and defending the coast of France from the Allied invasion. He recognized that defenses along the coast were weak and requested that German tanks be moved closer to the coast, but was overruled by Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt was responsible for the overall German command in the west. He disagreed with Rommel on the best strategy to repel the invasion and was dismissed by Hitler after the Allied success in Normandy. General Friedrich Dollmann was the commander responsible for defending the western part of Normandy. He faced the American forces that landed on Omaha and Utah beaches and was unable to prevent their link-up and expansion. General Hans von Salmuth was the commander responsible for defending the eastern part of Normandy. He faced the British and Canadian forces that landed on Gold, Juno, and Sword beaches and was unable to stop their advance.

Concluding Remarks

D-Day was the name given to the June 6, 1944, invasion of the beaches at Normandy. Many explanations have been given for the meaning of the term D-Day. According to the United States military, “D-Day” was an Army designation used to indicate the start date for a specific field operation. The military also employed the term “H-Hour” to refer to the time on D-Day when the action would begin.

D-Day was the largest seaborne invasion in history, and it resulted in a high number of casualties on both sides. The estimated number of Allied casualties was 10,000, including 4,414 confirmed dead. Among them, 2,501 were Americans. More than 5,000 were wounded.

The accomplishments of those who landed in Normandy and who fought through WW II battles deserve to be remembered by their countries and the world. We honor the many who lost their lives and are buried in cemeteries on the Normandy coast. They were young and prepared to die to protect a way of life they believed in. Many returned home physically and mentally injured for the rest of their lives. Others remain in unmarked graves throughout Europe. When they are found, remains are identified and repatriated with full honors to their country of origin. We must never forget the accomplishments of those who landed in Normandy, and those who fought through subsequent WW II battles. World War II was the deadliest military conflict in history, where an estimated 70–85 million military and civilians died. Veterans want all citizens of the world to understand the importance and price of freedom. Remember them and remember the importance of their courage to secure a better world. The memory of their courage and sacrifices must continue. The values they fought for to secure a better world must live on in all of us in our increasingly geopolitically complex world.

Further Reading

Drez, R.J., Remember D-Day: The plan, the invasion, survivor stories, National Geographic, Washington, DC, 2015.

Eisenhower, D.D., Crusade in Europe, Doubleday, 1948.

Falconer, J., and S. Watson, D-Day Operations Manual: ‘Neptune’, ‘Overlord’ and the Battle of Normandy – 75th Anniversary Edition: Insights into how science, technology and engineering made the Normandy invasion possible, J.H. Haynes & Co. Ltd. UK, 2019.

Grint, K., D-Day Leadership Lessons For Business Leaders. Core Insights, Warwick Business School, The University of Warwick. September, 2018. D-Day leadership lessons for business leaders | News | Warwick Business School (wbs.ac.uk)

Grint K., The Hedgehog and the Fox: Leadership Lessons From D-Day. Leadership, 10(2):240-260. 2014.

Tillman, B., D-Day Encyclopedia, Regency Publishing, Washington DC, 2004.