Seventy-five years ago this month, on 26 December 1933, Edwin Howard Armstrong received four patents for frequency modulation (FM) inventions. Our present FM radio owes more to Armstrong than to anyone else: he developed much of the technology himself, and he worked for two decades to establish FM broadcasting in the United States.

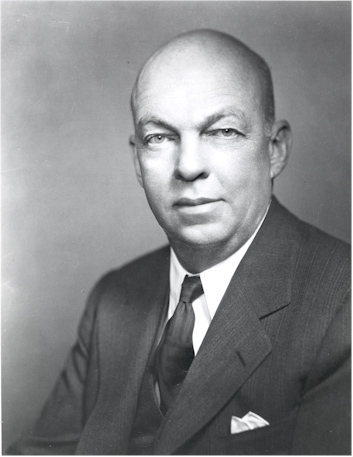

Edwin Howard Armstrong was born in New York City on 18 December 1890, and studied electrical engineering at Columbia University under the celebrated Michael J. Pupin. Radio was Armstrong’s passion, and about a year before he graduated in 1913, he devised a circuit that revolutionized the radio art. Using a triode as an amplifier, he fed back part of the output to the input, and thereby obtained much greater amplification. Armstrong made a further discovery with this circuit: just when maximum amplification was obtained, the signal changed suddenly to a hissing or a whistling. He realized this meant that the circuit was generating its own oscillations, and thus that the triode could be used as a frequency generator. The first of these discoveries — of a powerful amplifier — vastly increased the sensitivity of radio receivers, while the second — of an oscillator — led to the use of the electron tube in transmitters and also in receivers for an added function, heterodyne reception.

In 1901, Reginald Fessenden had introduced to radio the heterodyne principle: if two tones of frequencies A and B are combined, one may hear a tone with frequency A minus B. Armstrong used this principle in devising what came to be called the superheterodyne receiver. The essential idea is to convert the high-frequency received signal to one of intermediate frequency by heterodyning it with an oscillation generated in the receiver, then amplifying that intermediate-frequency signal before subjecting it to the detection and amplification usual in receivers. RCA marketed the superheterodyne beginning in 1924, and soon licensed the invention to other manufacturers. It became — and remains today — the standard type of radio receiver.

In the early 1920s, Armstrong turned his attention to what seemed to him, and to many other radio engineers, as the greatest problem, namely, the elimination of static. He wrote, “This is a terrific problem. It is the only one I ever encountered that, approached from any direction, always seems to be a stone wall.” Armstrong eventually found a solution in frequency modulation, which is a different way of impressing an audio signal on a radio-frequency carrier wave. In the usual technique, known as amplitude modulation (AM), the amplitude of the carrier wave is regulated by the amplitude of the audio signal. With frequency modulation, the audio signal alters instead the frequency of the carrier, shifting it down or up to mirror the changes in amplitude of the audio wave. He soon found it necessary to use a much broader bandwidth than AM stations used (today an FM radio channel occupies 200 kHz, twenty times the bandwidth of an AM channel), but doing so gave not only relative freedom from static but also much higher sound-fidelity than AM radio offered.

With the four patents for his FM techniques that he obtained in 1933, Armstrong set about gaining the support of RCA for his new system. RCA engineers were impressed, but the sales and legal departments saw FM as a threat to RCA’s corporate position. David Sarnoff, the head of RCA, had already decided to promote television vigorously and believed the company did not have the resources to develop a new radio medium at the same time. Moreover, in the economically distressed 1930s, better sound quality was regarded as a luxury, so there was not thought to be a large market for products offering it.

Armstrong did gain some support from General Electric and Zenith, but it was largely on his own that he carried out the development and field testing of a practical broadcasting system. He gradually gained the interest of engineers, broadcasters, and radio listeners, and in 1939 FM broadcasts were coming from twenty or so experimental stations. These stations could not, according to FCC rules, sell advertising or derive income in any other way from broadcasting, but finally, in 1940, the FCC decided to authorize commercial FM broadcasting, allocating the region of the spectrum from 42 MHz to 50 MHz to forty FM channels. In October of that year, it granted permits for 15 stations. Zenith and other manufacturers marketed FM receivers, and by the end of 1941, nearly 400,000 sets had been sold.

U.S. entry into the war brought a halt both to the granting of licenses for FM stations and to the production of FM receivers. After the war, FM broadcasting was dealt a severe blow when the FCC made one of its most unpopular decisions, moving the FM spectrum allocation (to the range from 88 to 108 MHz) and thus making obsolete the 400,000 receivers, as well as the transmitters of dozens of broadcasters. This allocation, however, allowed for two and a half times as many channels, and the FM industry slowly recovered, though it did not enjoy rapid growth until the late 1950s. In the late 1970s, FM broadcasting surpassed AM in share of the radio audience, and by the end of the century, its share had grown to three times that of AM broadcasting.

Among the many honors Armstrong received were the Edison Medal of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE) and the Medal of Honor of the Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE). These were the highest honors of those two predecessor organizations of the IEEE. Sadly, the last years of Armstrong’s life were darkened by continual patent litigation, and he committed suicide on 31 January 1954.

Frederik Nebeker is Senior Research Historian at the IEEE History Center at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. Visit the IEEE History Center’s Web page at: www.ieee.org/organizations/history_center.