Walt Hubbard was in Seattle when Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans in August 2005. As director of the King County (Wash.) Office of Emergency Management, he had a professional interest in what was unfolding.

He also felt a personal connection to the storm victims. Many were clinging to life on rooftops and overpasses, or taking refuge in the Superdome. Many would lose their lives.

No part of New Orleans was hit harder than the Lower Ninth Ward. Hubbard’s family is from that part of town. He later found out that one of his uncles died in Katrina.

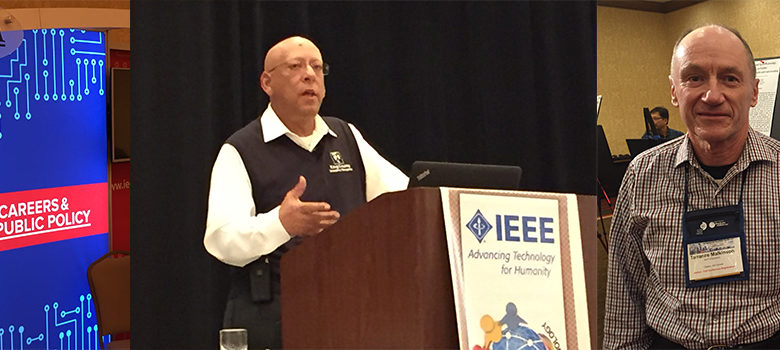

“I’m a child of the Ninth Ward,” said Hubbard during his keynote address at the IEEE Global Humanitarian Technology Conference (GHTC). He was among more than 300 people from around the world who came to the DoubleTree by Hilton Seattle Airport in mid-October.

If Hubbard had wanted to remain and hear some of the other speakers, or attend a paper presentation, he couldn’t. He and his staff spent much of the day (14 October) preparing for the remnants of a typhoon that was heading toward Oregon and Washington. Fortunately, the wind, rain and loss of power turned out to be less than expected.

The top priority of the Emergency Management Office Hubbard leads is public safety. It specializes in preparing for disasters, responding to them, and helping people recover. It also addresses many homeland security issues.

“Our mission is to secure access to emergency services for the two million people [who live in King County],” he said. “The only way to accomplish that mission is by working closely with government, industry and nonprofits to act quickly, when things go bad.”

Hubbard appreciates the key role electrical engineers play in mitigating and responding to calamities. For example, EEs design transmission, generation and distribution systems that are more resistant to weather and man-made acts of violence.

Smart Grid technologies can alert electric utilities in real time when electricity goes out, so a crew can be deployed to restore power. Resilient communications systems keep vital information flowing. Another key is using language the public can easily understand.

“In this world, with an astonishing amount of data analysis coming to us at an unbelievable clip,” Hubbard said, “it’s more important than ever to make sure that the right information is getting to the right hands in a way where it could be put to good use.

“In my world, the term “greatest good,’ translates into saving lives and restoring communities.”

Former IEEE Region 6 Director Mike Andrews said engineers offer much more than technology.

“We have created a problem-solving approach that is, by the way, unique to the engineering disciplines,” Andrews said. “If you talk with politicians, if you talk with English majors, if you talk with others in non-technical fields, they don’t necessarily bring that to the table.

“So one of our successes is the ability to solve problems, and get the right resources, and the right people to the right spot.”

Lamenting, Connecting to Tragedy

When Hubbard thinks about his job of protecting the public, his mind wanders back to New Orleans. During Hurricane Katrina, water as high as 12 feet spilled into the Lower Ninth Ward. It remained for days.

Ten years later, the largely African American community has not fully recovered. Empty lots and overgrown grass dominate the landscape.

“It’s an original and cultural neighborhood that in many ways no longer exists,” Hubbard said.

A few days before Katrina struck the Gulf Coast, Hubbard spoke by phone with a 15-year-old niece, who told him she and other relatives were going to a local hotel. Knowing that was not a good option, he told her they needed to leave town.

They did the day before the storm made landfall.

“I looked at that experience, and I followed it very closely, because that’s my sort of family heritage,” Hubbard said. “The attitudes and the values that my parents instilled in me came from their growing up there. So, losing the Ninth Ward, and knowing what that meant culturally to my family, was something that was really important.”

Many people consider that aftermath of the hurricane, which left more than 1,800 people dead and displaced hundreds of thousands, worse than the storm itself. Hubbard still laments the cultural devastation, particularly in the Ninth Ward.

“It’s been an object lesson for me; and one that is somewhat personal, even though I left there at an early age,” he said. “[It’s something] that I continue to track. There’s still a lot of work to be done there.”

Serving Our Nation

Hubbard’s service as an officer in the U.S. Army has also influenced his desire to help people. His time overseas, he said, was particularly valuable–and showed him there are myriad ways to accomplish something.

“That experience dramatically broadened my cultural lens and gave me a better appreciation for the term, “vulnerable populations,'” Hubbard said. ” “There are sections of this country that really need support and help. And the more diverse our population becomes, the more language-challenged we are, the more cultural bridges we have to build.”

Following his 20-year military career, he served as director of a Seattle health care clinic that he described as providing “uncompensated care to a broadly diverse community.” The experience he gained from each of his jobs has “influenced his approach as an emergency manager.”

“With respect to our equity and social justice piece here [at the conference], which is really about access, availability, and reaching out to portions of the community, I think that [my] military experience was a gift,” said Hubbard, who retired as a lieutenant colonel. “I’m fortunate to have had an opportunity to be part of that.”

Preparing for Calamity

To help prepare for the major earthquake that is expected to strike the Pacific Northwest, officials from three states and one Canadian province participated in the emergency management exercise Cascadia Rising in June. The scenario was designed to simulate the effects of a 9.0 magnitude earthquake and resulting tsunami.

“It crossed Northern California, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia,” Global Humanitarian Technology Conference Chair and IEEE Fellow Joe Decuir said. “How do we mitigate a disaster that’s going to happen?”

Unlike most natural disasters, earthquakes don’t provide scientists and public officials with enough time to adequately warn people. The last devastating temblor to strike the Cascadia Subduction Zone was in 1700. An earthquake along the 800-mile offshore fault line shakes the region every 200 to 500 years.

The suddenness and “unknown nature” of an earthquake concerns emergency planners and first responders.

Hubbard termed Cascadia Rising, a “punch to the gut.”

“We are going to be overwhelmed by demand. How can we get resources into place as quickly as we can to be able to satisfy that–because folks are going to be out of support for a long time. Schools, jobs, the economy. There’s going to be a long financial impact to this area.”

A 9.1 magnitude temblor and tsunami struck Indonesia in 2004. The dead numbered more than 228,000.

“Something like that will happen here. It is inevitable,” Decuir said “I may not be alive to [see] it, but hey, it’s going to happen.”

Hubbard agrees:

“All the models that we have looked at “¦ have been telling us this could be very devastating. So we need to be prepared.”

Chris McManes is IEEE-USA’s public relations manager.