In 1876, the United States of America experienced a complex mix of noteworthy events, including the Centennial International Exhibition held in Philadelphia to celebrate the country’s birth and the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, as well as one of the most disputed presidential elections in history. The latter brought an end to the federal government’s already-waning initiatives to reconstruct the South after the Civil War. The former created a festive venue for displaying some of the technological wonders of the age. The Corliss Steam Engine towered over visitors looking at the Statue of Liberty’s arm, the Remington Typographic Machine, the Edison Electric Pen, an array of industrial and agricultural machinery, and Alexander G. Bell’s mysterious contraption: the telephone. That same year, Thomas A. Edison built a research laboratory twenty-five miles south of New York City along the Pennsylvania Railroad, a short distance, but a world away, in the village of Menlo Park, New Jersey. Edison declared he would produce “a major invention every six months, a minor one every six weeks” at his invention factory. He and his team of “muckers” spent the next four years working on a variety of projects, including the carbon transmitter for the telephone receiver. Yes, “can you hear me now” was a pertinent question long before cellular telephone service. In addition to improving the telephone, Edison invented the phonograph, or talking machine. He demonstrated the cylinder phonograph at the Scientific American office in New York on 7 December 1877, and within a few months this new wonder brought international fame and garnered Edison the title, “the Wizard of Menlo Park.” Today, however, most remember Edison as “the inventor of the light bulb,” or more accurately the inventor of a practical and economical incandescent lamp and a direct current electric light and power system.

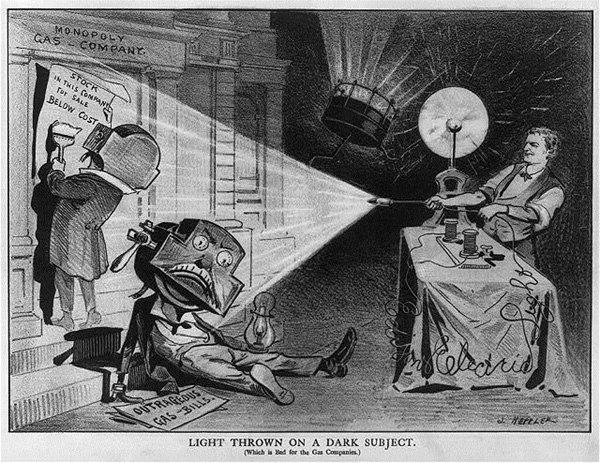

By the summer of 1878, Edison was exhausted by both constant work and new-found celebrity, so he took a western vacation after accompanying a scientific expedition to Rawlins, Wyoming to observe the eclipse of 29 July, and to measure the heat of the sun’s corona with his recently invented tasimeter. In late August, back home at Menlo Park, Edison pursued a new interest: electric lighting. A few weeks later, in the New York Sun (16 Sept. 1878), he exclaimed “I have it now;” meaning he figured out how to make an electric lamp of much lower candle power than the arc light and suitable to indoor use. He also announced plans to create a complete electric lighting system to replace manufactured gas. These statements created a tidal-wave of anxiety amongst investors in manufactured gas companies. The humor magazine, Puck, published a cartoon “Light thrown on a dark subject (Which is Bad for the Gas Companies),” (23 Oct. 1878) depicting Thomas Edison with his newly-invented electric light bulb illuminating the gas company monopoly personified by two men with gas-meter heads. Many gas companies had terrible reputations for poor service and quality, high rates, shady political dealings, and unethical business practices. Gas stock prices tumbled and the gas companies were justifiably unnerved because Edison studied their technology and industry, figured out their limitations, and attacked them head-on. He also concentrated on the heart of the artificial illumination market, domestic lighting, because it was 90 percent of the market and it was very profitable for manufactured gas companies. For the time being, street and outdoor illumination remained the domain of the arc light and manufactured gas industries

Although Edison believed he solved the problem of subdividing light, his announcement to displace manufactured gas with a complete electric light system was woefully premature. Much work remained, but he attracted the attention of men associated with Western Union and Drexel Morgan & Company, and on 16 October 1878, they incorporated the Edison Electric Light Company in New York. This company provided monetary support for research and development and in return received control of Edison patents. On 5 October, an exhilarated Edison wired Theodore Puskas, his European representative, “The electric light is going to be a great success. I have something entirely new. Wm. H. Vanderbilt and friends have taken it in this country and on Monday next advance $50,000 to conduct experiments.”

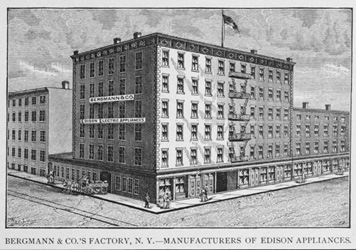

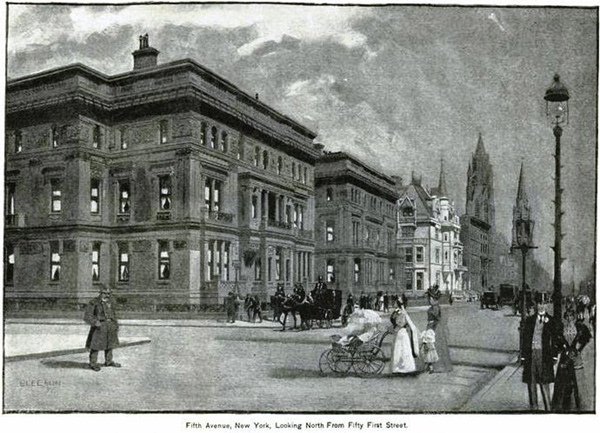

This public demonstration was only the beginning of Edison’s endeavor to develop and commercialize electric light and power technology. He expanded the laboratory staff and worked on a complete electric light system, but these efforts involved more than “the system.” Edison also created the electrical manufacturing industry by founding companies to make components, including lamps, conductors, dynamos, and light fixtures and to sell and install isolated plants, and later, central stations. The Edison Electric Light Company remained the parent, patent-holding and licensing company, and a new separate corporation, the Edison Company for Isolated Lighting, was created to sell plants of a “self-contained character.” Edison sold isolated plants in private residences, offices, commercial and industrial establishments, and other venues, including the first commercial marine incandescent electric lighting plant, installed aboard Henry Villard’s SS Columbia in late April 1880. That same year, William H. Vanderbilt visited Edison’s office at 65 Fifth Avenue “saw the light, and decided that he would have his new house lighted with it.”3 This massive residential complex, known as the “Triple Palace” at Nos. 640 and 642 Fifth Avenue and No. 2 West 52nd Street, consisted of three mansions, one for Vanderbilt and his wife, and one each for his married daughters, Margaret Fitch and Emily Vanderbilt Sloane.4 Famous interior designer, Christian Herter, head of interior decorating at Herter Brothers, designed a showplace for Vanderbilt’s art collection. Vanderbilt’s son-in-law, Hamilton McKown Twombly, then in charge of the telephone department of Western Union, closed the contract for an isolated plant. Edison remembered, “After a while we got the boilers and engines and wires all done, and the lights in position, before the house was quite finished, and thought we would have an exhibit of the light. About eight o’clock in the evening we lit it up, and it was very good. Mr. Vanderbilt and his wife and some of his daughters came in, and were there a few minutes when a fire occurred. The large picture gallery was lined with silk cloth interwoven with fine metallic thread. In some manner two wires had got crossed with this tinsel, which became red-hot, and the whole wall was soon afire. I “ordered them to run down and shut off. It had burst into flame, and died out immediately. Mrs. Vanderbilt became hysterical “We told her we had the plant in the cellar, and when she learned we had a boiler there, she said she would not occupy the house. She would not live over a boiler. We had to take the whole installation out.”5 After this mishap, Vanderbilt ordered the isolated plant removed in 1882, and he even complained about the bill. However, Mrs. Vanderbilt was alarmed by living atop a boiler not the incandescent lamp itself, so a few years later, the mansions received service from the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of New York’s second central station.

Although isolated plants sold well, the Wizard of Menlo Park was frustrated because he had a vision analogous to manufactured gas distribution plants with the incandescent lamp as the nucleus of a central station system of electric light and power. In 1910, Edison’s biographers, Frank L. Dyer and T.C. Martin, wrote: “From first to last Edison has been an exponent and advocate of the central-station idea of distribution” [But]”demands for isolated plants for lighting factories, mills, mines, hotels, etc. began to pour in” [T]he inquirers desired to purchase outright and operate themselves” It had not been Edison’s intention to cater to this class of customer until his broad central-station plan had been worked out”[However,] the steady call for supplies and renewals would benefit the new Edison manufacturing plants.”6 By May 1883, 330 Edison isolated plants were in operation and the Edison Electric Light Company was quite content simply leasing the rights to Edison’s patents.7 Unlike building central stations, selling an isolated plant required limited financial risk and it brought no long-term responsibility.

Shortly after the Menlo Park demonstration, the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of New York was incorporated in 1880 with one million dollars of capital stock. This new company leased Edison’s patents from the parent company and paid for the construction of the Pearl Street central station in lower Manhattan. Some men had experience wiring and installing simpler electrical equipment such as telephones, district-messenger calls, burglar alarms, and house annunciators, but there were no artisans, mechanics or electricians, with experience in this line of work. Now Edison had to train a workforce, so he started a night school at 65 Fifth Avenue. Students from technical schools and colleges applied, too. Charles L. Clarke, from the Menlo Park laboratory, took charge of engineering work and instructed these beginners in general engineering problems. By 1882, fearful of low-quality installation methods, Edison also penned a manual for wiring and installation work for isolated plants, and a standardizing committee was created to test and report on all existing and proposed devices. In turn, men trained the Edison-way constructed a showcase central station on Pearl Street in New York City.

The Pearl Street central station, built in a prominent location, commenced operation with much fanfare. The “Miscellaneous City News” column of The New York Times reported that, on 4 September 1882, the “Jumbo” dynamos were started at 3:00 PM at the Edison Electric Illuminating Company of New York’s central station at 257 Pearl Street. The lights were turned on around 5:00 PM, but the true spectacle was not appreciated until it became dark nearly two hours later. With the simple turn of a thumbscrew, a lamp was turned on emitting a light “soft, mellow and grateful to the eye,” making rooms “as bright as day.” Indeed, “Mr. Edison had at last perfected his incandescent light, had put his machinery in order, and had started up his engines, and last evening his company lighted up about one-third of the lower City district in with THE TIMES building stands.” Now Edison was going to push the work as rapidly as possible, extending service to the rest of the district laying between Pearl Street and the East River and Spruce and Wall streets. 8

The Pearl Street station was supposed to attract others desiring an Edison central station plant in their own community. The Edison Electric Light Company expected these local entrepreneurs to raise the cash, license Edison’s patents, and then purchase Edison equipment. However, the Wizard of Menlo Park trusted neither his technology nor his financial success to the less-than-enthusiastic parent company and inexperienced workers. Edison argued, if done properly and on a large enough scale, central station distribution would be commercially successful. Samuel Insull, Edison’s private secretary recalled, “When it was found difficult to push the central-station business owing to the lack of confidence in its financial success, Edison decided to go into the business of promoting and constructing central-station plants, and he formed “the Thomas A. Edison [Central Station] Construction Department”9 By May 1883, he made two essential managerial decisions, including choosing to emphasize the sale of central stations, and consolidating divisions of other companies into the Construction Department. He established the Construction Department as an independent and unincorporated company to promote and install central stations using the Edison system, and used local agents to form local electric light companies and attract local capital to go into business in competition with their local gas companies. In exchange for a license to use Edison’s patents, local illuminating companies paid 20% of their capital stock and 5% in cash and agreed to buy Edison equipment at 12% above cost.10

In the spring of 1883, Edison presided over the structural reorganization of his new company, and grappled with determining the quickest and most cost-efficient manner to build central stations. Initial plans and time schedules predicted that a central station and distribution system could be completely installed and ready to supply light in two months (in retrospect, this was unrealistic). His strategy was based on breaking construction into various distinguishable processes and organizing them as departments. In addition, he also intended to have numerous central stations in various stages of installation, thereby ensuring the entire company was never without work. He decided to be a contractor for central stations, so with his crew of engineers, technicians and laborers, he set out to bring his electric light system to America.

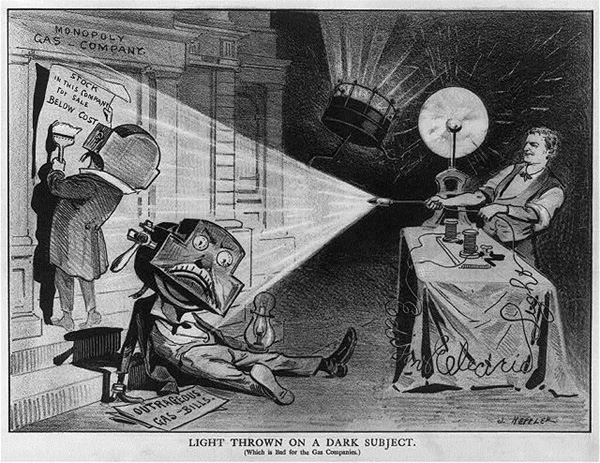

If Edison merely invented a practical incandescent lamp, the story would have ended with the execution of his first patent application for a high-resistance carbon filament (U.S. Pat. 223,898) on 1 November 1879. Out of necessity, Edison and a few key associates founded companies to manufacture parts for the Edison system of electric lighting, and frustration and desperation drove Edison to “”take charge of the village plant business because””; In April 1883, Samuel Insull wrote Edward Johnson: “The Edison Electric Light business is not run well [and] so much impressed is Edison by this fact that he as practically left his Laboratory [and] now makes my Office his Headquarters [and] is attending to purely business matters”; [H]e could see that this Village Plant business would go to ruin unless he came up [and] attended to matters. He says he has been told again [and] again that they could get nothing satisfactory from the Executive Officers of the Light Co. So Edison decided to “drop science [and] pursue business.'”11

It was Edison, the inventor and the businessman that personally financed the Thomas A. Edison Central Station, Construction Department, presiding over it from early May 1883 until 1 October 1884, when the Edison Company for Isolated Lighting took over this line of work. In a little more than one year, the Construction Department built thirteen central stations in the northeastern and midwestern sections of the United States. In addition, by October 1885, thirty-one Edison central stations were in operation or under construction in the United States, with fourteen local companies organized in the past year.12 The following year, promotional literature distributed by the Edison Electric Light Company bragged “Now, even ‘our friends, the enemy’ (the Gas companies) acknowledge that the problem of supplying the Edison Incandescent Light for the service of the individual consumer, by a system of house-to-house lighting is a practical success, and are content with expressions of doubt as to our ability to make a profit in competition with them.”13 Business expanded rapidly, and by 1888, 169 Edison central stations were scattered across the United States and its territories. However, those early central stations, albeit plagued by problems because they were built as inexpensively as possible and usually constructed and managed by inexperienced men, laid the cornerstones of the investor-owned electric utility corporate enterprises we know today.

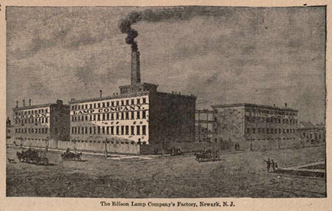

TABLE 1. Central Stations Built by the Thomas A. Edison Central Station, Construction Department.

| STATION14 | COMMENCED OPERATION | CAPACITY (Lights) | POPULATION (1880) | ESTIMATED COST in US DOLLARS [2015 value] | DISTRUBUTION SYSTEM |

| Sunbury, PA | 4 July 1883 | 500 | 4,077 | $14,500 [$345,283] | Overhead (“village plant”) |

| Shamokin, PA | 22 Sept. 1883 | 1,600 | 8,184 | $30,000 [$714,286] | Overhead |

| Brockton, MA | 1 Oct. 1883 | 1,600 | 13,608 | $31,000 [$738,095] | Underground |

| Lawrence, MA | 20 Oct. 1883 | 1,600 | 39,151 | $32,527 [$774,452] | Underground |

| Fall River, MA | 18 Dec. 1883 | 1,600 | 48,961 | $41,810 [$995,476] | Underground |

| Tiffin, OH | 3 Jan. 1884 | 1,000 | 7,879 | $18,000 [$439,024] | Overhead |

| Mt. Carmel, PA | 22 Jan. 1884 | 500 | 2,378 | $14,560 [$355,122] | Overhead |

| Bellefonte, PA | 4 Feb. 1884 | 800 | 3,026 | $17,072 [$416,390] | Overhead |

| Hazelton, PA | 11 Feb. 1884 | 1,000 | 6,935 | $20,864 [$508,878] | Overhead |

| Newburgh, NY | 31 March 1884 | 1,600 | 18,049 | $41,193 [$1,004,707] | Underground |

| Middletown, OH | 5 April 1884 | 500 | 4,538 | $13,969 [$340,707] | Overhead |

| Piqua, OH | 28 April 1884 | 1,000 | 6,031 | $23,186 [$565,512] | Overhead |

| Circleville, OH | 14 June 1884 | 1,000 | 6,046 | $27,803 [$678,122] | Overhead |

References

- Francis Jehl, Menlo Park Reminiscences, Vol. 1 (Dearborn, Michigan: Edison Institute, 1937), 357.

- Jehl, 422.

- Israel, Paul B., Louis Carlat, David Hochfelder, Theresa M. Collins, and Brian C. Shipley, editors, The Papers of Thomas A. Edison: Electrifying New York and Abroad, April 1881 ” March 1883, Vol. 6 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007), Appendix 1: Edison’s Autobiographical Notes.

- “The Lost Vanderbilt Triple Palace, 5th Ave and 51st Street,” Daytonian in Manhattan, 28 June 2014. https://daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com/2014/06/the-lost-vanderbilt-triple-palace-5th.html (Accessed: 2 March 2016)

- Frank Lewis Dyer and Thomas C. Martin, Edison: His Life and Inventions, 1910; reprint (NP: Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc., 2005), 223 ” 224.See also Israel, Appendix 1: Edison’s Autobiographical Notes, “Lighting Vanderbilt’s House,” 815-816 (notes written in Edison’s hand in 1909). Mrs. William H. Vanderbilt is Maria Vanderbilt.

- Dyer and Martin, 222-223.

- Israel, et. al, Thomas A Edison Papers,” Vol. 6, Appendix 2: Isolated Lighting Plant Installations, May 1883, 833.

- “The Miscellaneous City News, New York Times, 5 Sept. 1882.

- Dyer and Martin, 256-257. See also Paul Israel, Edison: A Life of Invention (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1998), 220 ” 225.

- Israel, 221. See also Memorandum: Village Plants, 29 March 1883, Doc. 2417 in Israel, et.al, Thomas A. Edison Papers, Vol. 6, pg. 809.

- Samuel Insull to Edward H. Johnson, 3 Apr. 1883, LM 3:120 (TAED L M003120; TAEM 84:103), Thomas A. Edison Papers, Vol. 6, pg. 809-810, FN1

- Edison Electric Light Company, Report of the Board of Trustees to the Stockholders at their Annual Meeting, 27 October 1885, Thomas A Edison Papers, Microfilm Edition (TAME), 96:5 and 147:907.

- Primary Printed Series, Edison Electric Light Company, Circulars, Central Stations, 1886 (Edison System of Incandescent Electric Lighting from Central Stations) TAEM, 96:41,

- Inflation Indicator, DaveManuel.com (accessed: 10 Feb. 2016) https://www.davemanuel.com/inflation-calculator.php?theyear=1870&amountmoney=175.

Mary Ann C. Hellrigel, Ph.D., is Institutional Historian and Archivist at the IEEE History Center.

Edison was nothing more than the privateer crowd with which he hung out with, such as the Morgans, etc. He stifled true innovation from Tesla and promoted ruthless marketing tactics such as those in the “War of the Currents.” His ‘light’ on the gas companies was his way into another monopoly backed by big investment bankers. You have to look behind the scenes to understand his true nature. Even the light bulb was discover by his hordes of staff using trial and error techniques (brute force) rather than empirical science. His showmanship is well known, but his craving for money and power is almost always never discussed openly.