Minicomputers are back, but then, they never really left. This year, marketers of personal computers the size of paperback books or grapefruits sell them as “mini computers” when compared to PCs from, say, 2005. Two to three years ago, the innovation of circuit boards a few square centimeters in area, enough to hold a microprocessor and some ports, resulted in classifying the Arduino microcontroller and Raspberry Pi as mini computers.

What is a minicomputer, anyway? Encyclopedia Britannica defines it as a computer “that is smaller, less expensive, and less powerful than a mainframe or supercomputer, but more expensive and more powerful than a personal computer.” Industry veteran Gordon Bell wrestled with the subject and hoped that people might distinguish between the “classic” and other minicomputers. Apparently neither contemporary marketers nor EB are paying attention. Type the question into Google and the first result, from Techopedia, includes Cory Jannsen’s historical summary, “Minicomputers emerged in the mid-1960s and were first developed by IBM Corporation.” Former IBM and Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) staff of a certain age may bristle over this statement, for the received history is that DEC initiated the minicomputer era with its PDP-8, while IBM ignored the category and leased its 1620 and 1130 simply as small computers. Others who remember even earlier, small, general purpose computers may also fume, for what does it mean for a technology to have “emerged”?

In one respect, Jannsen is correct-but ten years late. Because if we focus on its general purpose capability, human-scale size, and low price compared to mainframes, the first minicomputer is arguably the IBM 650. Debuting in 1953, it filled a niche, according to IBM’s press release, between the “”giant brains’ and the widely-used smaller machines”-that is, the calculators that gave International Business Machines its name. The use of punched cards for decimal input boosted sales unexpectedly with business users less familiar with binary programming. Instead of the projected sales to 50 industrial and research consumers, it became the first computer to sell more than 1,000 units, doubling that number in ten years.

Still, the 650 system cost over $100,000, even with educational discounts, and required an air-conditioned room with supported flooring. Two companies followed IBM’s lead, however, and innovated cheaper, small, general purpose, digital computers with which a user could interact directly and which needed no special housing. In 1956, Librascope sold the first of 450 LGP-30s, which weighed 800 pounds and drew 300 watts. The University of Alberta paid $40,000 for an LGP-30, “Flexowriter,” and punched-card reader used by four departments. By 1961, Bendix Corporation had sold more than 300 of its $51,000 G-15s, a “medium speed,” refrigerator-sized computer that a programmer could access with a typewriter or digital inputs. Sales justified innovation of the transistorized G-20. Bendix offered 1,000 programs and routines, along with “a vigorous G-15 user’s exchange group” and a nationwide network of hardware and software support. Bendix could have taken its minicomputer further, but instead sold its computer division to Control Data Corporation (CDC) in 1963. CDC installed 410 of its $60,000 CDC 160 and 160A minicomputers, designed by Seymour Cray, by the end of 1964.

DEC, on the other hand, made its name in small computers. Founded in 1960 to exploit innovations in electronic components and their assembly, it made general purpose computers cheap enough to expand the industry’s markets. Introducing the PDP-8 in January 1965, DEC minced no words in the price war with Raytheon Computer’s 250, the Friden 6010 Electronic Computer, and Computer Control’s DDP-116, all advertised in the same issue of Datamation: “PDP-8: The $18,000 Digital Computer.” Honeywell was far more discreet when touting its $21,000 H20 “Digital Control System” in a two-page ad that never mentions “computer.”

As for IBM, its engineers developed the 1620 as a scientific minicomputer at the end of the 1950s, and delivered 2,000 of them in ten years. Compared to IBM’s mainframes, the 1620 didn’t need a special room or a staff to operate it. In February 1965, IBM followed up with the 1130. The first ad echoed the PDP-8’s selling points and its own brand: “Powerful new computer. Only $695 a month. Only from IBM.” The text explained that IBM “tailored the 1130 to the needs of the small-budget engineering or scientific worker,” while it could also assist in computerized typesetting and small-business accounting. Within a year, IBM had 2,000 orders for the 1620; users fondly remember using it in high schools and universities to learn how to program.

Despite the proliferation of minicomputers in the second half of the 1960s, however, people almost never used the term. A review of Datamation issues shows that advertisers and writers usually called the desk-sized and then desktop computers “small” or “fourth generation,” thanks to large scale integrated (LSI) circuitry. As for DEC, the standard tale related by former executives is that, in 1967, one of their London-based peers wrote to his colleagues in Massachusetts that everything was “mini” there: the Cooper Mini, the miniskirt, etc. He suggested that DEC apply the term to their bestselling computer, which was small in size and cost compared to mainframes. DEC never called its PDP-8s minicomputers in its 1960s advertising, however, even as it shrank the size and price of newer models. In 1967, it began offering prospective customers copies of its “540-page Small Computer Handbook and Primer” (which, curiously, isn’t available online or in print). By then, DEC had established itself by expanding a market that IBM had pioneered: industrial controls, where computers reacted to data from a process and adjusted accordingly. Two years later, Datamation reported that DEC had “delivered more than 3,500 small computers.” (July 1969, p. 149) To be sure, PDP-8s also went to universities and labs, a smaller but more visible market.

The term gained industry traction only in 1969, when Datamation published a lengthy article on minicomputers for control applications in March, and computer pioneer and publishing entrepreneur Isaac Auerbach added Minicomputer Reports to his Computer Technology directories. The same year Computers and Automation devoted its December issue to the subject. It first appears in the IEEE Xplore database in 1970, while Edson de Castro and a few others began using “minicomputer” and “small computer” interchangeably in other publications in 1968.

Where, then, did the term originate? The first known appearance is in Datamation‘s January 1967 “New Products,” which announces Control Data’s overlooked 449-2 “mini-computer.” The company delivered a developmental model to the U.S. military the following year. It weighed twelve pounds, including display and keyboard, and fit in an overcoat pocket. Three years later, Data General wholeheartedly called its Nova a “mini computer” while DEC was still oscillating between “small” and “mini” in its ads.

Even as DEC finally embraced “Mini-Peripherals for Mini-Computers” in January 1971 for its “more than 10,000 mini-computers delivered,” IBM remained focused on marketing applications. That didn’t deter some staff from observing in 1981 that “the IBM 1620 and 1130 clearly were minicomputers before the name was coined in the late 1960s.” Sales of these alone matched those of DEC in the 1960s, with some 10,000 1130s installed globally, and IBM installed more than 25,000 System/3 minicomputers between 1969 and 1974. Editors failed to see a difference. Datamation included IBM’s products in a 1971 minicomputer survey, and in 1976, the Palm Beach Times headlined news of IBM’s Series/1: “IBM Introduces New Minicomputer.”

The diffusion of minicomputers led to a now-forgotten trifurcation of computer classes in 1969. Redcor Corporation touted its RC 70 as a “midi” class computer, alongside the SDS Sigma 2, HP 2116B, and other fast 16-bit computers, between a “maxi” like UNIVAC’s 1108 and a “mini” like the PDP-8. Similarly, “The Other Computer Company,” Honeywell, introduced its Model 3200 as its “low-priced entry in the medium-range computer field” for the 1970s, and Scientific Control promoted its SCC 5700 as a “midi-computer.” DEC touted its PDP-15 as the Picasso of “medium size computers.”

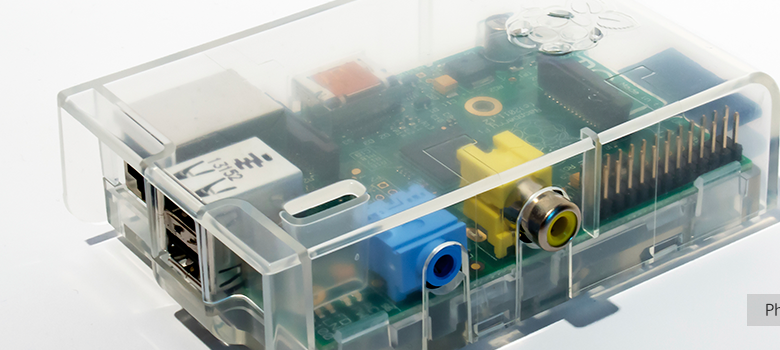

Better known is the complication occasioned by the adoption of microprocessors as the basis for desktop computers. General purpose computers no longer required a 19-inch rack. The Homebrew Computer Club’s newsletter reported on Sonoma County Minicomputer Club meetings in Cotati, California. John Titus’s Mark-8 and the Altair were touted as minicomputers on the covers of Radio-Electronics in July 1974 and Popular Electronics in January 1975, respectively. Titus learned to program in FORTRAN II on an IBM 1620 at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and used a DEC PDP-8/L at Virginia Tech. He described his device as “a complete minicomputer which may be used for . . . data acquisition, data manipulation and control of experiments.”

The name didn’t stick to what people were also calling micro, home and personal computers. Instead, as these proliferated and surpassed the capabilities of 1960s minis, DEC, IBM, and others scaled up minicomputers’ capacities during their “Silver Age” in the 1980s. By century’s end, however, only IBM and Hewlett Packard continued to offer minicomputers, as servers for work stations. In the 2000s, Microsoft, OQO, and Paul Allen explored what Wired called the “Return of the Minicomputer”-“Mini-PCs” or netbooks. In the other new computer class, a smartphone adopter likened it in 2009 to “walking around with a minicomputer in my pocket.” Now that we’re back where we started, however, minicomputer purists can take some solace that Next Thing’s new $9 CHIP is not a mini but a “micro-computer.”

Alexander B. Magoun, Ph.D., is outreach historian at the IEEE History Center at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J. Visit the IEEE History Center’s Web page at: https://www.ieee.org/about/history_center/index.html.

Very good article. you can visit minicomputer