A discussion of ethical behavior at the theoretical level can be a yawning turnoff. It makes little difference whether it is with regard to engineering, corporate management, medicine, or, indeed, any field in which ethical dilemmas are common.

So it is no surprise that engineering schools and others interested in encouraging debate and discussion of ethical issues are moving away from generalized theory in favor of real-life ethics case studies.

When actual case studies are tackled, several points emerge. First, ethically challenging situations are seldom confined to a single field. And an action or solution that may be considered acceptable in one profession may be deemed unethical in another. As a result, what are nominally labeled engineering ethics cases will often also involve corporate and sales/marketing ethics, as well as customer expectations of proper behavior in a testy or confrontational situation. In the attempt to resolve ethical issues, fault and liability may be important components. Intent can play a role, too. And while there are sometimes winners, there are always losers.

The Airbag Situation

The ongoing airbag safety issue provides a complex case study replete with ethics implications at several levels. As I write this, Honda has just announced it will recall 2.6 million cars in the United States. Along with recalls by other automakers it was prompted by the reported deaths of five motorists and the injury of several others from exploding metal shards during the deployment of airbags supplied by Takata Corp. Worldwide, more than 16 million cars from several makers may be involved. Besides Honda, they include Toyota, Nissan, BMW, and Chrysler.

The Takata airbags use an ammonium nitrate propellant that, when triggered in a crash, may react with an unexpectedly violent explosion that tears its canister apart and drives its pieces through the airbag. When the recent failures were reported to Takata, its executives said it could not replicate the fault.

Nevertheless, a 1995 Takata patent application (patent issued in 1996), stated that a major problem with the use of ammonium nitrate is that it undergoes several temperature-dependent crystalline phase changes. Temperature cycling can cause expansion and contraction of the ammonia nitrate crystals. They can expand and change shape and thus are “totally unacceptable in a gas generant used in airbag inflators” resulting in an inflator that “might even blow up because of the excess pressure…” The patent went on to suggest several modifications to alleviate the problem, as, for example, adding a small percentage of potassium to the ammonium nitrate. The patent notwithstanding, Takata did not begin to use ammonium nitrate until 2001. Prior to that it used sodium azide, noted for its toxicity, and, later, tetrazole, which proved to be both costly and in short supply.

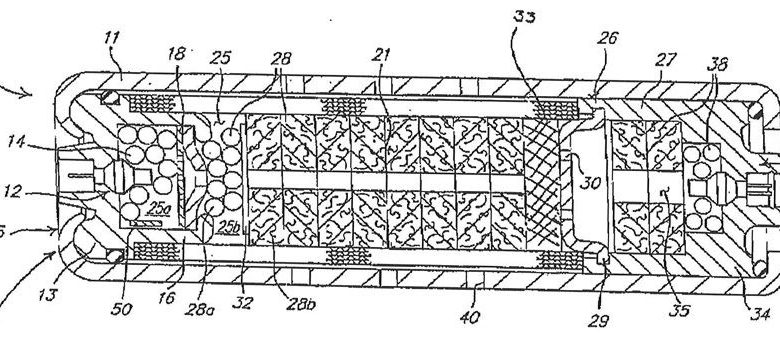

The company acknowledges that production quality control is extremely important, and that keeping the propellant moisture-free both during its manufacture and after it is installed in a car is critical. In a 2006 patent application it noted that unless moisture-absorbing material is added, the inflator could rupture “due to extremely high internal pressure.” A cross-sectional illustration from the patent application (above) suggests one possible redesign of the cylindrical inflator that might alleviate the problem. More recently, in a patent application filed in 2013, the company proposed coating the pellets with paraffin.

Many questions remain unanswered. During the recall, will it be possible to determine if a particular airbag is potentially defective? Takata has suggested certain manufacturing flaws that have subsequently been corrected were at fault. Might this mean that only those cars containing the subject propellant need be recalled? If, on the other hand, all 16 million must be replaced, Takata has indicated it does not have the production capacity to do so at a reasonable pace. Can other airbag makers (e.g., Autoliv) aid in the replacement task, and must they use the ammonium nitrate technology? (None currently do so.)

Will litigation arising from injuries and deaths be abetted by the cautionary descriptions of ammonium nitrate’s shortcomings that are spelled out in Takata’s patent applications?

And what was the role of the Automotive Systems Laboratory in Farmington Hills, Michigan, identified as Takata’s research lab? It is named as having filed the pertinent patents.

What responsibility do the various car makers who installed the questionable airbags bear? And what about the engineers, chemists, and quality-control experts involved in the design, test, and approval of the defective airbags? In mid-December of 2014, ten automakers met in Michigan to organize an independent investigation by an outside expert to test these inflators in order “to promote the safety, security, and peace of mind for all customers.”

During the difficult and costly resolution of the recall, it is not very likely that many of the issues will be referred to as ethics-related. Rather, they will be labeled management, design, quality-control, marketing, legal, financial, and reputational issues.

Yet ethics is pervasive in many aspects of the recall, both in its cause and its execution. It should prove to be an exceptional, multifaceted case history, perhaps as widely used in university courses in practical ethics as has been the 1986 Challenger explosion.

Postscript

The Takata recall followed the 2014 General Motors recall of 2.6 million vehicles caused by an ignition switch defect that prevented airbag deployment. This was not an airbag fault per se, but resulted in injuries and deaths when airbags were not activated due to power failure. The defect was known to GM in 2003, but was not publicly revealed until 2014, making it a candidate for another ethics case study.

It is widely recognized that even working airbags can injure or kill passengers who are termed “out of position,” referring to children, the elderly, or those who differ significantly in shape or size from the ideal driver (172 lb. and 5’9″) for whom the airbag is designed and tested. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimated that from 1990 to 2007 airbags killed 191 children and 39 women who were 5’2″ or less in height. And while 33,561 highway deaths were accounted for in 2012, airbags were reported to have saved 2213 lives the same year.

On balance, there seems little doubt that both the airbag and the ways in which it is tested can be improved.

Resources

- Process For Preparing Azide-Free Gas Generant Composition, U.S. Patent 5,531,941, July 2, 1996 (Automotive Systems Laboratory, Inc.)

- Nonazide Gas Generant Compositions, U.S. Patent 5,872,329, Feb. 16, 1999 (Automotive Systems Laboratory, Inc.)

- Phase-Stabilized Ammonium Nitrate, U.S. Patent 6,872,265 B2, Mar. 29, 2005 (Autoliv ASP, Inc.)

- Self-Healing Additive Technology, International Patent Application WO 2014/084869A1, Pub. Jan. 5, 2014, Filed Dec. 2, 2013 (TK Holdings, Inc.)

- Gas Generator (Propellant Cushion), U.S. Patent Application, U.S. 2006/0220362 A1, Pub. Oct. 5, 2006, Filed Mar. 30, 2006.

- Airbag Inflation with External Filter, U.S. Patent 6,341,799 B1 Jan. 29, 2002 (Automotive Systems Laboratory, Inc.)

- Tabuchi, H., “Airbag Compressant Has Vexed Takata for Years,” The New York Times, Dec. 10, 2014.

- Saporito, W., “Safe or Sorry: A Massive Recall Shows the Damage from Defective Air Bags,” Time, Dec. 15, 2014.

- Marsh, R., “Takata has struggled with airbag problems since late 1990s,” https://www.cnn.com (retrieved Dec. 12, 2014).

- Snavely, B., “Automakers join to pursue Takata bag probe,” https://usat.ly/1DjefpQ (retrieved Dec. 12, 2014).

- “GM Didn’t Warn Customers About Ignition Switch Problem For 11 Years,” HuffPost Business, Dec. 14, 2014. (retrieved Dec. 14, 2014)

Donald Christiansen is the former editor and publisher of IEEE Spectrum and an independent publishing consultant. He is a Fellow of the IEEE. You can write to him at donchristiansen@ieee.org

I’m not knowledgeable about this field, but originally I heard that airbags were designed for 250 lb unbelted drivers. It strikes me as an ethical decision – protect the large idiot (unbelted) and endanger the smaller more cautious individuals; versus assuming a smaller population with the possible result that larger/less cautious individuals may be injured.