Ida Henrietta Hyde was born in Davenport, Iowa, on 8 September 1857 to Meyer and Babette Heidenheimer, who had changed their name to “Hyde” after immigrating to the United States from Germany. From an early age, Hyde took a great interest in education, attending classes at the Chicago Athenaeum at age sixteen. While working long weeks, she was able to save up enough money to attend one year of college in 1881, passed the county and Chicago teachers’ exams, and taught in the Chicago area until 1889. Inspired by a teachers seminar at Martha’s Vineyard, she wanted to pursue a career in science, and applied to Cornell, where she graduated in 1891 with an AB in Zoological Science. Shortly afterwards, she was awarded a scholarship to Bryn Mawr, where she conducted research at the U.S. Fish Commission at Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

Hyde was awarded an Association of Collegiate Alumnae fellowship to study in Europe, initially studying at the University of Strassburg. She was advised by Professor Alexander Goette, director of the zoology department, to petition the Reichstag for the privilege of being allowed to work for her doctorate, and eventually withdrew the petition after the idea was strongly contested by several members of the Strassburg (modern-day Strasbourg) faculty. Afterwards, she later applied to the University of Heidelberg, and while she was permitted to take the examination for the doctorate, she was not permitted to attend lecture or laboratory classes, and had to work independently from loaned books and lecture notes taken by the professor’s assistant. Despite these setbacks, she earned her doctorate in 1896.

After returning to the United States, she was hired she under William Townsend Porter in the Department of Physiology at Harvard University in 1896, and co-founded the Naples Table Association for Promoting Scientific Research by Women in 1897. Hyde founded the physiology department at the University of Kansas in Lawrence in 1899. At the time, it was a rarity for a woman to be employed as faculty at a coeducational college. In 1902, she was the first woman elected to the American Society of Physiologists. She taught at the University of Kansas until she was forced out of her position in 1916. In 1918, she took a leave of absence for wartime duties, and extensively traveled for three years, formally retiring in 1920.

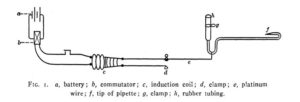

In 1918 and 1919, Hyde conducted experiments on unicellular organisms and echinoderm eggs, and found it necessary to construct a micro-pipette that was more accurate than the existing Barber or Chamber apparatuses. Barber’s apparatus was developed in 1912, and building on his work, she invented a micro-electrode, which consisted of a Barber pipette modified for unipolar stimulation. This consisted of glass tubes about twelve centimeters long and six millimeters in diameter, drawn out to a bent tip, with pipettes containing mercury or an electrolytic solution, or a fine wire that would allow current from a battery to manipulate the meniscus of the mercury. The observations of the behavior of mercury led to the idea that the micro-electrode could be adapted for the injection or extraction of minute quantities of substances from unicellular structures while transmitting electrical stimulation to an individual cell. This ability was an improvement over the Barber and Pratt designs, which could not simultaneously stimulate the interior of a cell while drawing from or injecting material into the cell.

While Hyde’s electrode is the earliest known micro-electrode for intracellular work, her experiments in this area were not widely published, and she received little recognition for the invention in her lifetime. Hyde only published a single paper on the subject in Biological Bulletin, and similar principles were independently rediscovered in the 1940s by Judith Graham and later Ralph Gerard, who was nominated for a Nobel prize in the 1950s for his work on the micro-electrode.

During her retirement, Hyde was still active in research and publishing until her death on 22 August 1945. She published her paper on the micro-electrode in 1921, and established a scholarship fund at the University of Kansas to benefit women pursuing careers in the sciences, which has been awarded to more than one hundred women. Hyde’s broad research career made her a pioneer in many areas related to physiology, her micro-electrode research in particular being an early achievement in engineering in medicine and biology.

References and Further Reading

- Center for the History of Medicine at Countway Library, Harvard University, “Dr. Ida Henrietta Hyde, 1896, and Dr. Myrtelle May Canavan, 1923” https://collections.countway.harvard.edu/onview/exhibits/show/women/early-faculty/dr–ida-henrietta-hyde-and-dr-.

- Emily Taylor Center for Women & Gender Equity, University of Kansas, “Ida Henrietta Hyde,” https://emilytaylorcenter.ku.edu/pioneer-woman/hyde.

- Hyde, Ida Henrietta, “Before Women Were Human Beings,” Journal of the American Association of University Women, June 1938.

- Hyde, Ida Henrietta, “A Micro-Electrode and Unicellular Stimulation,” Biological Bulletin, Vol. 40, No. 3, Mar., 1921.

- Johnson, Elsie Ernest. “Ida Henrietta Hyde: Early Experiments,” The Physiologist, Vol. 24, No. 6, 1981.

- Kass-Simon, Gabriele, “Biology is destiny” in Women of Science: Righting the Record, Indiana University Press, 1993.

- Physics Today, “Ida Henrietta Hyde” https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/10.1063/PT.6.6.20190908a/full/

- The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, “Ida Henrietta Hyde,” https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/hydeida-henrietta