Two years ago, G. Pascal Zachary wrote an article in IEEE Spectrum on the absence of heroes in engineering. Defining heroes as those who triumph over adversity-“whether personal, institutional, or technological”-and contribute “to the social and cultural well-being of humanity,” he argued that engineering as a field will not appeal to young people as a profession without such exemplars, or to the general public as a subject worthy of attention. He contrasted the profession’s lack of heroes with the military and sports professions, where men and women sacrifice themselves for their nation or perform great symbolic feats of skill against improbable odds. In 2015, Spectrum followed up with a series of profiles celebrating its readers’ choices for engineering heroes.

Zachary and Spectrum‘s search resembles that of others seeking heroes. These efforts often conflate heroism with altruism in that they overlook the classic hero’s willingness to risk everything, up to and including his or her life, for the greater good of society without expecting a reward. They have proliferated across American society, thanks to Hollywood’s commodification of comic book superheroes and corporate marketing of professional and collegiate sports. Who can pretend, however, that movie actors and professional athletes are more than highly skilled, well-paid entertainers?

We don’t have engineering heroes because we don’t have a heroic culture. Next to the online edition of Zachary’s article, Spectrum promotes a story on Ajay Bhatt, “Intel’s Rock-Star Inventor.” Americans esteem risk-taking entrepreneurs and celebrities, where marketing, not virtue, has a reward. Contrarily American engineering culture emphasizes teamwork over individualism in educational settings and corporate projects. Because there are ample material benefits for taking technical risks, by definition it’s additionally difficult to be a heroic engineer in a start-up, corporation, or university. On the other hand, the material rewards for majoring in engineering put paid to Zachary’s concern about appeal. Young people want to become engineers, but often find that the education is much harder, or duller, than other profitable fields. So what we really want are not heroes, but role models for our children: engineers who succeeded financially and socially because of their work ethic, persistence, passion, and determination, among other qualities.

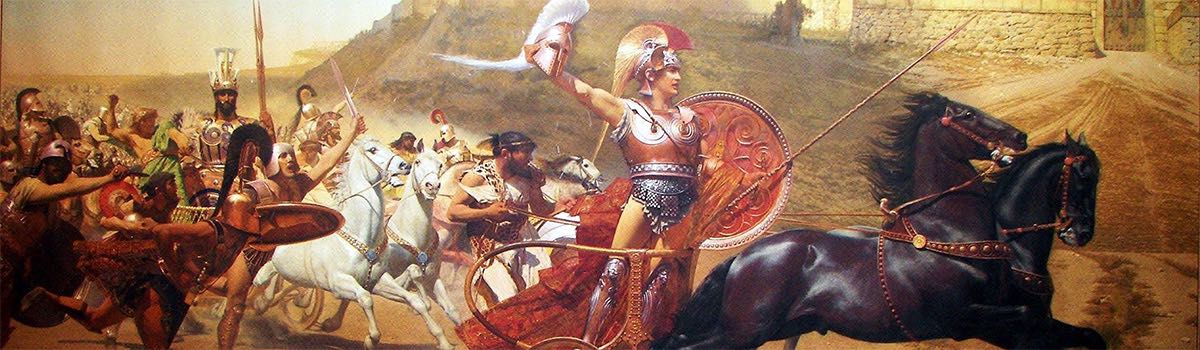

The difference between hero and role model becomes clear when we consider the historical roots and classical definition of a hero. Heroes in ancient Greece arose out of a culture steeped in people’s struggles with their gods, who represented the chaos and mysteries of the world. To support their side, Greeks invented sacrificial demigods, who struggled and suffered alone against great odds to accomplish goals with no expectation of reward. Heroes were personified in warriors like Achilles and Odysseus. Achilles was the world’s greatest hero, but he suffered the tragic, fatal flaw of a mortal heel. Odysseus fought well, but his heroism resided more in the clever and brave ways he overcame the obstacles that the gods put in his journey home. Both men are worthy of respect, yet we wouldn’t necessarily wish for Achilles’s anger issues or Odysseus’s reputation for self-interest. Greek heroes are now hardly role models, given their superhuman origins and very human character flaws.

Achilleion, Corfu, Greece

Originally installed at Westminster Abbey, London;

now located at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh

The same question applies on the American side. Samuel Morse and Edison gained heroic stature, thanks to their accomplishments, their self-promotion, and a society eager to show off democracy’s success. They, too, benefited handsomely from their innovations, and were followed in the public eye by culturally celebrated captains of industry-Carnegie, Rockefeller, Ford-who capitalized on engineering developments in steel, oil and automobiles.

Hearth and Home magazine

As for the IEEE, since its founding in 1884, the vast majority of engineers have come from comfortable or middle-class backgrounds. They trained in standard, mathematically based curriculums and worked in large institutions: think of Claude Shannon at Bell Labs or Zachary’s Vannevar Bush at Harvard. Even if we could identify this generation’s Watt, engineering is no longer as tangible and comprehensible as an engine where steam goes in and work comes out. In IEEE fields, engineers put the invisible to work as a source of power, light and information. Barring a shock, electrons have to be assumed and then understood mathematically, which makes public comprehension a challenge. In computing, there is even less visual appeal, much less understanding: try justifying the heroism in typing code on a keyboard.

The greatest engineering struggles lie in the greatest technical challenges, and then persuading colleagues, superiors or investors to accept or buy a revolutionary solution. Living legends like engineering entrepreneurs Dean Kamen or Elon Musk, who resemble the “rock star” inventors of the Industrial Revolution, are disqualified from heroic status for the same reason of profit. On the other hand, that could be the reason to esteem them as role models.

As historian Ruth Schwartz Cowan told Zachary, modern heroes should be those who overcame social or cultural discrimination as well as technical challenges. We should also look for people from impoverished or working class circumstances, who then accomplished something remarkable. In her success at overcoming gender bias and helping to pioneer the development of software, Grace Hopper qualifies for the modern pantheon. So too does Roger Boisjoly, an IEEE-USA honoree. He risked his career to blow the whistle on the cupidity and cover-up that resulted from the disastrous engineering flaw he’d warned of in the Space Shuttle. Can you propose others? Modern engineers merit society’s praise and publicity for their technical and financial accomplishments, but only a few its heroic laurels.