The bursting of the dot.com bubble in 2000 prompted students to reject computer science programs. Enrollments plummeted with the crash. But colleges are now scrambling to keep up with the major’s year-after-year enrollment growth.

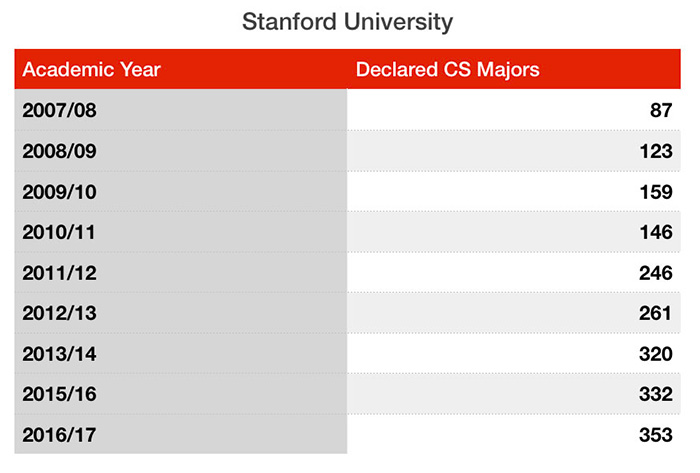

Take Stanford University. In the 2007-08 academic year, Stanford had 87 declared undergraduate computer science majors. That was near the trough of the great decline in computer science enrollments.

But since then, the number of declared majors at Stanford has grown in each year and by the 2016-17 academic year, Stanford counted 353 majors. This is now the school’s top undergraduate major.

Credit: Data from Stanford University

Stanford is not alone. Dartmouth College’s computer science program has quadrupled, but that doesn’t tell the entire story. Many students, who are pursuing a variety of undergraduate degrees, are making computer science part of their study. These students now consider data analytics and coding as fundamental parts of their field.

“I don’t think anybody expected what we are seeing now,” said Hany Farid, a professor of computer science and chair of the department at Dartmouth.

By the time they graduate, 75 percent of Dartmouth’s students have either taken an engineering or computer course, said Farid. An introductory computer science course teaches a student how to code in Python. Students also study data structures to learn how to represent and manipulate data, as well algorithmic analysis that teaches them how to assess whether one algorithm is better than the other in terms of runtime complexity.

“I can tell you that 50 percent of accepted students to Dartmouth have expressed some interest in computer science – that’s insane,” said Farid.

This increasing demand for computer science education is nationwide.

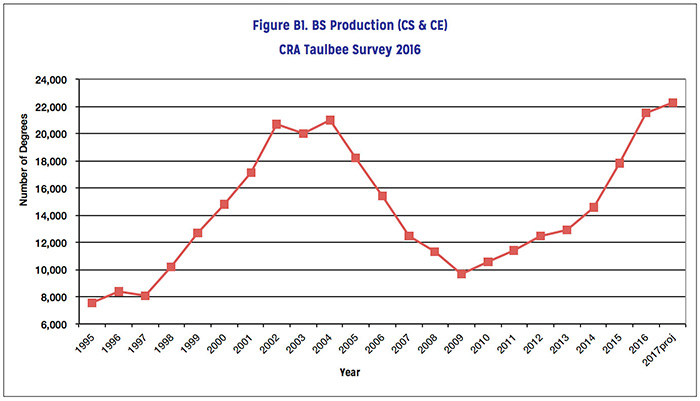

In the 2003-04 academic year, the number of undergraduate degrees awarded by Ph.D-granting institutions surveyed annually by the Computing Research Association (CRA), fell from more than 20,000 to about 10,000 in four years.

The latest findings from the CRA’s Taulbee Survey projected 22,000 undergraduate computer science students at Ph.D-awarding schools, a gain of 120 percent from the trough.

Credit: Computing Research Association Taulbee Survey

Credit: Computing Research Association Taulbee Survey

But is there any risk that an economic downturn could, once again, turn students away from computer science? The rise of start-up tech firms with valuations of more than $1 billion – so-called unicorns – such as Uber and Airbnb has given rise to speculation that this could be another tech bubble.

Jay Ritter, a professor of finance at the University of Florida’s Warrington College of Business Administration, believes the situation today is much different from 18 years ago.

“Although the valuations on certain ‘unicorns’ are high, overall the tech sector’s valuations can be justified without requiring extremely optimistic assumptions,” said Ritter, in an email.

“I expect jobs for good coders and other people with strong technical backgrounds to continue to be plentiful. I’m more worried about the job outlook for people without these skills,” said Ritter.

Farid was teaching computer science at Dartmouth College during the dot-com era. He believed at that time interest in computer science was mirroring the bubble. “The excitement about computing felt a little premature,” he said.

Today, it’s completely different, said Farid.

Dartmouth graduates about 1,000 students, in total, a year. This year it graduated 100 computer science majors, about four times the number of those who graduated with the degree five years ago.

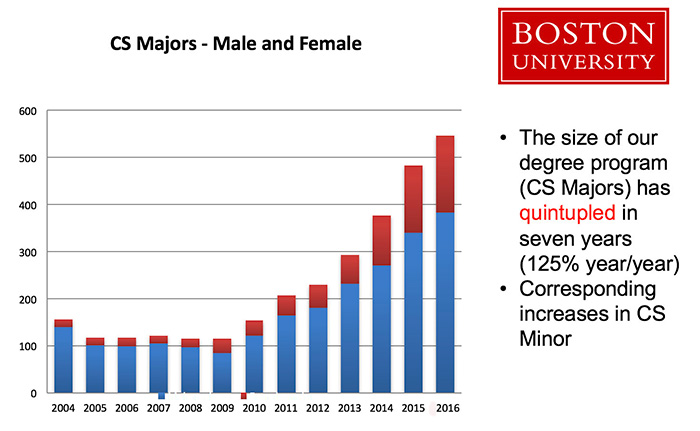

In 2009, Boston University’s computer science program had about 110 declared undergraduate computer science majors. This fall it will have more than 550, said Prof. Mark Crovella, the chair of the university’s computer science department.

Credit: Boston University

Credit: Boston University

This interest in computer science is far in excess – and much deeper – than the dot-com era when measured by credit hours. The typical course at BU is four credit hours. In 2000, students in total were taking about 3,000 credit hours of computer science classes. That’s a measure of all the enrollments in the classes. It’s now at about 6,000 credit hours.

“In other words the overall interest in computer science at BU is currently at about twice the level it was at the peak of the dot.com year,” said Crovella.

Crovella believes computer science enrollments will level off. “My expectation is that demand has to saturate at some point,” he said. Nonetheless, interest in the program will remain high, he said.

“The old notion that you are just sort of a drone who sits in a cubicle is starting to give way to the idea that you’re someone who has an impact on the world, who changes society, who can create things that are useful and valuable,” said Crovella.

The sense of satisfaction that students are getting out of computer science “is no longer driven just by the satisfaction of solving a difficult algorithmic problem or difficult mathematical problem, but it can be driven by the satisfaction of seeing people using what you do and potentially creating tools that help people,” said Crovella.

Gender balance is improving as well. In 2005, women accounted for about 15 percent of computer science enrollments at BU, but Crovella expects women to account for 30 percent of computer science declared majors in the upcoming year. The number of women enrolling in introductory courses was 47 percent last year.

Salaries for new grads are rising, too, which suggests that demand is real. The Hay Group division of Korn Ferry, an executive search firm, reported in May that salaries for new grads seeking jobs as software developers were $63,036, a 1.5% increase from last year.

Another survey by The National Association of Colleges and Employers reported that the average starting salary for computer science graduates this year was expected to reach $65,540, a nearly 7 percent increase.

Prof. Mehran Sahami, who is the associate chair for education in the computer science department at Stanford, believes the computer science enrollment trend will continue, he said, in an email. Helping stimulate interest are the ongoing national efforts to increase computer education in K-12, as well as the launch in 2014 of the Advanced Placement Computer Science Principles Course by the College Board. He sees a lot of job market demand as well.

“As the numbers bear out, the interest in computer science has grown tremendously and shows no signs of crashing,” said Sahami.

Patrick Thibodeau is an award-winning news reporter focused on high-impact, traffic-driving, exclusive stories that connect with readers. For more than 20 years, he was senior editor at Computerworld, where he covered technology-related public policy issues, including offshore outsourcing, globalization, IT careers and workforce.

When I signed up to get my degree in 1981 in Electronics Technology, the school hosted at least one interviewer a day for the last three months.

When I graduated in 1983, the school hosted a single interviewer in that three-month span.

Markets can be oversaturated. There was a severe shortage of techs in 1981, but the schools produced too many.

I have no idea if that can happen with computer science today, but in a strange coincidence, that 1983 saturation of techs is why I became a programmer.