Ada Henry Van Pelt was born in 1838 in Princeton, Kentucky. The daughter of a banker, Major C.B. Henry, Ada had single handedly saved her father’s business and fortune during the Civil War. As Confederate troops were approaching, Ada had concealed her father’s savings in the folds of her hoopskirt, which enabled her to sneak the money out of the bank, past the army, and into a secure spot in their house where it remained safe from looting. Her brother, Colonel A.P. Henry, commanded the 15th Kentucky Cavalry Regiment during the war, and she married Captain Charles E. Van Pelt, of the 48th Kentucky Volunteer Mounted Infantry Regiment, in 1864. After the war, the couple moved to Nebraska, where she was one of the founders of the Lincoln City library. In 1889, after her husband’s death, she moved to California.

It was at this time that Van Pelt directed her efforts to inventing, and her first success was in 1890 with U.S. Patent #420,841, for improvements in permutation locks, designed for use on post-office lock boxes, doors, and jewel-cases, capable of three thousand different combinations. In 1892, she patented a letter box for the outside of houses, (U.S. Patent #471,918) which would display a signal indicating there is a letter in the box for the postal worker to collect. In 1902, she patented an improvement on an oil burner (U.S. Patent #724,761A) with William A. Laufman, which was designed for cooking and heating, specifically operating in a fashion which was smokeless, odorless and noiseless.

While living in Oakland, Van Pelt frequently crossed the San Francisco Bay to get to San Francisco by ferry, at the time the only route to get between the two cities. During her trips, she noticed several inefficiencies in the ferries’ engine operation, and observed a substantial loss in power in the fly-wheel mechanism. She set out to invent a device which would prevent the crank of the engine pin stopping on a dead center and would start anew in the same direction it was running at the time steam was shut off. Her ideas and observations were met with jests and derision from her male friends and colleagues, and Van Pelt was told that if her ideas were feasible, engineers who had spent decades studying steam engines would have already figured out a solution. Not discouraged by these remarks, Van Pelt built a steam engine in her Oakland sewing room, where she started to experiment with pendulums and steam engines. Conducting her work in secrecy over the course of ten years, Van Pelt developed a device which used a weighted oscillating beam with swinging pendants, rather than a fly-wheel. Van Pelt’s design was far more efficient and did not result in the same loss of power that previous fly-wheel designs experienced, and she patented her invention (U.S. Patent #1,002,610A) shortly after she moved to Los Angeles in 1910. In the Nebraska State Journal, the reception of her invention was described as having “many mechanical engineers have viewed the device, and all have expressed surprise that a principle so simple should be developed so long after the invention of the steam engine, and still more surprise that the discoverer should be a woman.”

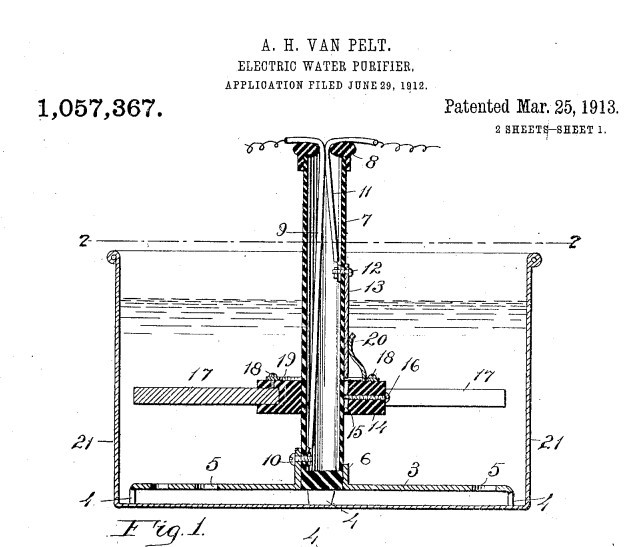

After this patent, Van Pelt turned her attention to electrical technologies and patented two improvements for water purification using electrolysis, a process in which electricity is used to decompose water into oxygen and hydrogen gas. Early work on the isolation of oxygen and hydrogen had been accomplished in the 1770s by English chemist Joseph Priestley, and around 1807, Humphry Davy had used a voltaic pile to employ electrolysis on various molecules, and isolated potassium, sodium, barium, calcium and magnesium. However, these early devices that used electricity to decompose a water molecule were not practical or cost efficient for widespread use in the home. Van Pelt’s first patent relating to electric water purification, U.S. Patent #1,020,001, filed in 1911, described the apparatus as a pair of tubular electrodes which sit on a hollow base that contains a reticulated plate. The current passed between the two electrodes breaks down some of the water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen, and the oxygen in a gaseous state, percolates through the organic impurities and kills them, thus purifying the water. The purified water then is allowed to drain into the base, where it passes through a filter that can easily be changed. Holding roughly three gallons of water, her device combines the filtration mechanism with the purification chamber to encompass both functions in a singular device, as she notes that just filtration of water alone does not kill any bacteria which may be present. Her second patent for electric purification of water, U.S. Patent #1,057,367, was designed to be “of such a character as to be portable and applicable for use in small vessels, so as to adapt it for domestic and other uses.”

Both her water purification patents were cited as late as the 1990s, and in describing her inventions, the publication Popular Electricity referred to her as “The Woman Edison” for her ingenuity. In 1912, she was made an honorary member of the French Academy of Science, and in addition to her invention work, Van Pelt frequently gave lectures, and was active in the Red Cross and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, where she served as editor for its weekly publication the Pacific Ensign for six years, greatly expanding the paper’s influence. At the time of her death, on 7 August 1923, she was the oldest member of the Ebell Club of Los Angeles, an educational and philanthropic organization founded by women, where she was the organizer of the Club’s dramatic section and served as curator emeritus. Her funeral services were held at the Club, where she was given special honors.

Bibliography and Further Reading

“Women Inventors,” Hardware: A Review of the American Hardware Market, Volume 20, November 25, 1899, p. 24

“L.A. Woman Member of Academy of Sciences,” Los Angeles Herald Vol. 39, No. 66, December 17, 1912, p. 17

“Last Rites for Mrs. Van Pelt at Ebell Club,” Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1923, Part 2, p. 20

Modern Electronics, Vol. 6, No. 5, August 1913, p. 490 https://worldradiohistory.com/Archive-Modern-Electrics/Modern-Electrics-1913-08.pdf

“Mrs. Van Pelt as an Inventor,” Nebraska State Journal, October 25, 1908, p. 22

“The Woman Edison,” Popular Electricity, Vol. IV, No. 12, April, 1912, p. 1118

“Mrs. Van Pelt Has Resigned,” San Francisco Call, Vol. 81, No. 47, January 16, 1897, p. 14

US Patent #420,841A, “Permutation-lock,” 1890 https://patents.google.com/patent/US420841A

US Patent #471,918A, “House Door Letter Box,” 1892 https://patents.google.com/patent/US471918A

US Patent #724,761A, “Oil-burner,” 1902 https://patents.google.com/patent/US724761A

US Patent #1,002,610A, “Apparatus for utilizing momentum,” 1910 https://patents.google.com/patent/US1002610A

US Patent #1,020,001A, “Electric water purifier and filter,” 1911, https://patents.google.com/patent/US1020001A

US Patent #1,057,367A, “Electric water-purifier,” 1912, https://patents.google.com/patent/US1057367