Just over two months ago, right before the world became aware of the novel coronavirus that was to cause a global pandemic, Walt Disney Pictures—in a move that in hindsight was either brilliant or inappropriate—released a live-action film about an earlier epidemic. Togo tells the story of a lead sled dog who ran a critical leg of a cross-country dash to bring desperately needed medicine to the town of Nome, Alaska, in February 1925, just over 95 years ago.

Children’s movie fans will remember this as the same plot as that of a 1995 animated film, Balto, from Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment. Visitors to New York’s Central Park may recall a statue dedicated to Balto near the entrance to the Zoo. In fact, there were 20 drivers and teams involved in this amazing “Great Race of Mercy” as it has been dubbed, and there has been an ongoing debate as to who was more important, Togo who led the 18th and longest, most difficult leg, or Balto, who led the two final legs.

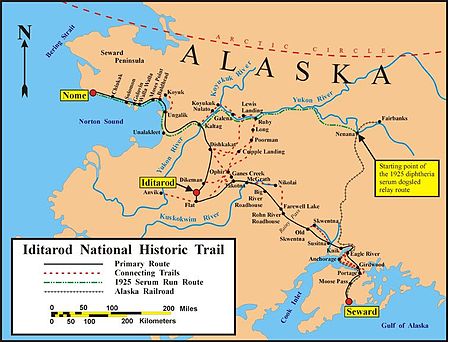

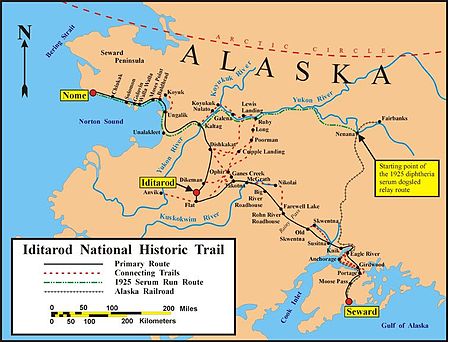

What I find more interesting than that contretemps, however, is what the story has to tell us about the use of technology in public health, an issue that we face today. Alaska was purchased by the United States from Russia in 1867, and, after a series of administrative schemes, it became a U.S. Territory in 1912. Nome, on Norton Sound, directly across the Bering Sea from Russia, was founded during the Alaska Gold Rush of the late 1890s, near the site of a native village. (See map at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1925_serum_run_to_Nome.)

What I find more interesting than that contretemps, however, is what the story has to tell us about the use of technology in public health, an issue that we face today. Alaska was purchased by the United States from Russia in 1867, and, after a series of administrative schemes, it became a U.S. Territory in 1912. Nome, on Norton Sound, directly across the Bering Sea from Russia, was founded during the Alaska Gold Rush of the late 1890s, near the site of a native village. (See map at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1925_serum_run_to_Nome.)

It soon became the largest city in Alaska, which was then an administrative District; in the 1900 U.S. census, the population was counted as 12,488. The seacoast town was largely reached and supplied by ship, but, because of sea ice, it could not be reached from December through April. The closest railway line ended at Nenana, 674 miles (1,085 km) to the east.

However, with the Gold Rush over, the population declined to 2,600 in 1910, while mining remained the main economic activity, with the Hammon Consolidated Gold Fields Company dominating the town. Because of Alaska’s exposure to Russia during the Gold Rush and its distance from Washington, D.C., the U.S. Army built an enormous network of telegraph cables between 1900 and 1904, the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS). The system included a series of wireless telegraph stations, including one of the largest at Nome, where an undersea cable landing proved prone to interference by the shifting of the sea ice. By 1921, when perhaps only 900 people lived there, Nome’s WXY used three continuous wave radio transmitters, two using modulated carbon arcs and one a 50-watt vacuum tube operating at 75, 83, and 500 kHz respectively.

On 20-21 January 1925, in a particularly harsh winter and with Nome’s isolation at its greatest, Dr. Curtis Welch diagnosed the season’s first cases of diphtheria in two Iñupiaq children who then died. Within a week, there were 20 cases and at least one death. Lacking any live antitoxin, a medical disaster threatened to overwhelm Welch, his four nurses, and the 25-bed Maynard Columbus Hospital in one of the most isolated communities in America.

Diphtheria is a deadly disease with mortality rates up to 10 percent, with symptoms that include sore throat, cough, and fever, which start two to five days after exposure. Like COVID-19, it is highly contagious and can be spread by direct contact, through the air, or on contaminated surfaces. Asymptomatic carriers can transmit the disease. However, it is the result of a bacterium, not a virus. Fortunately, medical scientists identified the bacterium in 1884, and quickly developed an antitoxin (the toxins produced by the bacteria cause the illness). A vaccine was created in 1923. Vaccination is now common in developed nations, and the disease, first described by the father of medicine, Hippocrates, in 5th century BCE Greece, is now rare.

After meeting with the town’s government and instituting a quarantine, Welch used the town’s telegraph and radio to alert other Alaskan doctors as well as the U.S. Public Health Service. There were a million units of antitoxin available in California that could be sent by rail to Seattle, but it would take weeks for steam ships to navigate the ice and storms en route to Nome. However, almost by a miracle, 300,000 forgotten units were located at the Anchorage Railroad Hospital, and were soon brought by rail to Nenana, 674 miles (1,085 km) from Nome. But the train could go no further. Trying to push the “high-tech” airplanes beyond their limits was considered but soon rejected.

In its commitment to universal service, the U.S. Post Office that year—only 20 years after the Wright brothers—experimented with airmail in Alaska, but the planes of the day could not stand the extreme climate of the winters there (and remember, there is very little daylight each day in Alaska at that time of year, and flying was all visual). The only three airplanes regularly operating in Alaska were based in Fairbanks, 570 miles (840 km)—double the range of these aircraft—to the east of Nome, stored for the winter while their pilots worked in the Lower 48 until spring. Officials decided against recruiting an inexperienced volunteer and turned instead in desperation to a technology that had not changed for four millennia.

The dog is humankind’s first domesticated animal, dating back at least 15,000 years. Over time, several prehistoric peoples began to use dogs for traction (that is, pulling vehicles such as carts or sledges). Around 2,000 BCE or even earlier, some societies in the Arctic regions of northeast Asia and northwest America began to use teams of dogs pulling sleds over snow and ice. From the 16th century on, European explorers, colonizers, hunters, and merchants adopted the transportation technology as the best adapted to the frozen north (Mush! comes from the French, Marchez!). The technique even returned to Europe by technology transfer, as northern European counties like Finland and Norway, adopted it for their more isolated regions. In Alaska, the dog sled industry resisted the incursion of airmail delivery well into the 1930s.

A plan was established for the antitoxin to head out by dogsled from Nenana to the village of Nulato, about halfway to Nome over the normal mail route, where it would be met by a dogsled team from Nome that would then complete the round trip. Each way usually took 30 days, but, in a race under better weather conditions, a record had been set from Nulato to Nome of four days. The high technology of radio alerted all of the drivers that, despite the season and the weather, they would be making a crucial run and should report to their stations. Twenty drivers and teams participated in the relay. Most of the interior legs were run by Native Americans whose ancestors had developed the technique. Some of the dogs died and many drivers suffered severe frostbite. Nevertheless, the serum left Nenana around 11 pm on 27 January 1925. Balto led his team into Nome around 5:30 am on 1 February, shattering previous records for the trip. The epidemic was averted. The latest medical technology was delivered by using the latest communications technology to coordinate the most ancient of transportation technologies. We need to remember, especially in troubled times, that newest is not always the best.

Michael N. Geselowitz, Ph.D., is staff director at the IEEE History Center at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J. Visit the IEEE History Center’s Web page at: https://www.ieee.org/about/history_center/index.html.