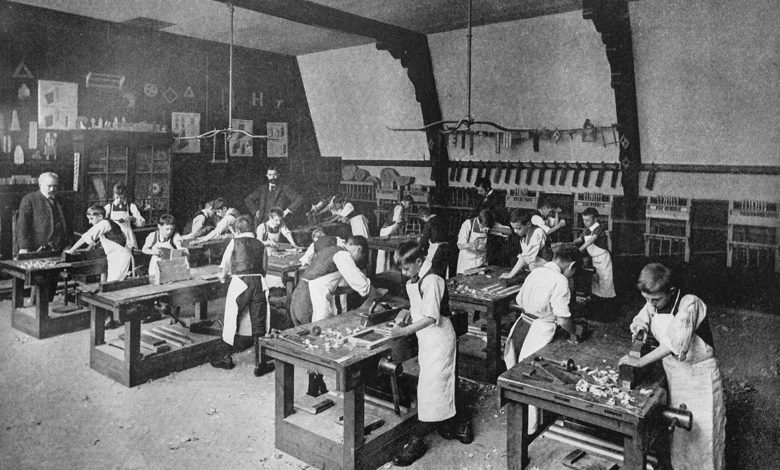

It was during the first half of the 20th century that the United States workforce shifted significantly from an agrarian base to an industrial base, largely as a result of the success of the industrial revolution. Congress passed the Smith-Hughes Act in 1917 to authorize federal funding of vocational education in U.S. schools. The act defined vocational education as preparation for careers not requiring a bachelor’s degree.

Historians view the early growth of vocational education as driven by two factors: industry’s need for skilled and semi-skilled factory workers, plus the increasing availability of public school students from farm families as well as immigrant students. Some, including educator and philosopher John Dewey, opposed the separation of vocational education from the mainstream as fostering class distinction within public education itself.

Nevertheless, there appeared to be no great evidence that the vocational school students themselves—even though they might be from low-income families with limited education—felt discriminated against. They saw the concept of training for a given industry and life employment in that industry as admirable.

Although I had no interest in attending a vocational school, while a student in the 7th and 8th grades of a traditional public school in the 1940s I was offered the opportunity to take manual training or shop classes that were part of a nearby vocational school. I jumped at the chance, as did all the other male members of my class. We had to hike a mile each way to and from the class in fair and foul weather, but never missed a class. Our projects were principally wood-working ones, and included learning how to operate a wood lathe. In high school, I chose the science option, but also elected to take courses in metal-working shop and mechanical drafting.

These proved advantageous when I applied for summer jobs during my high school years. The first was on a capacitor assembly line for Cornell-Dubilier. The next, assembling fractional horsepower motors and power tools at Kingston-Conley Electric Company, and the last, between my junior and senior years, doing time-and-motion studies in the newly-formed industrial engineering department of the Worthington Machinery Corporation.

Thus, without intending to, I had been pursuing a bit of “vocational training” on my own behalf. I now have little doubt that it was a factor in my ultimate choice of engineering as a profession.

The Big Change

By the last half of the 20th century (particularly in the middle years), it had become evident that those vocational schools that had not begun to incorporate the academic courses found in regular high school curricula were not preparing their students to meet the higher demands of increasingly complex industrial jobs. Technology itself was raising the knowledge and skill levels required for many occupations, and certain vocations were drastically changed or even made obsolete. Enhanced production technologies demanded more STEM training for vocational students. In response, the addition of academic studies involving reading, writing and advanced math began to enhance the value of vocational education. Students completing such studies had not only a greater chance of succeeding in a technically sophisticated manufacturing-dominant workplace, but also had an option of going on to college.

More Changes

The Vocational Education Act of 1963 sought the improvement of vocational education programs, and while continuing to fund new area vocational schools, began also to include occupational programs (e.g., business and commercial) in comprehensive high schools. It also supported vocational programs for the disadvantaged and disabled.

I shall not detail here the many reforms that began in the early 1980s. They were prompted largely by the increasingly poor performance of U.S. students both nationally and internationally, as well as by complaints by employers of the low levels of skills and general unpreparedness of high school graduates entering the workforce. To what extent each of the reforms have influenced vocational education, for better or worse, is debatable. Yet it began to seem that the label “vocational education” might become obsolete, due at least in part to its uneven practice over the years. It had been replaced in several states by the term “career and technical education” or “career and technology education.” An estimated 11,000 such programs are now offered in U.S. comprehensive high schools, and several hundred more in vocational-technical high schools.

The ultimate objective, as seen by many progressive educators, is the development of high schools that organize their courses so that students can readily develop both academic and vocational skills needed to compete for good jobs. The object of this “new vocationalism” is to enable students to gain a thorough knowledge of math, science and language, and to help them gain a level of proficiency to enter quickly into interesting and productive careers.

While there is general agreement on the need to integrate academic and vocational curricula, the best way to do so is yet to be determined. Might academic content be incorporated into existing vocational courses, or might existing academic courses be modified to make them more vocationally relevant? Seminar projects are yet another approach, in which students undertake a project that integrates knowledge and skills learned in both academic and vocational courses.

Can co-op education programs, similar to those originated and practiced by colleges and universities, be adapted to secondary schools? Students would be provided with jobs during the school year (part-time and/or summer) with local employers in their field of vocational interest. The student-employer matches would be arranged by a school coordinator.

The Future

Keeping pace with the increasing demands on vocational education has not proven easy for the educational establishment, and the ways of doing so have varied significantly.

In 2011, the U.S. Department of Labor awarded nearly $500 million in grants to community colleges for training and workforce development to help economically disadvantaged workers who are forced to change careers. The grants would enable community colleges and employers to partner in devising instructional programs that meet specific industry needs and provide pathways to good jobs. The program began with grants to 32 community colleges, with the intent to award a total of $2 billion over a 4-year period to schools across the United States. Careers to be targeted are those in high-wage, high-skills fields, including advanced manufacturing, transportation, health care, and STEM occupations.

Steps to merge academic and vocational studies have proven to be particularly desirable, although the many choices in vocational specialties (manufacturing, information technology, transportation, etc.) require that teaching technologies (e.g., the design of math problems) be varied according to the particular specialty. Eventually, just as universities consist of several individual schools in which to accommodate distinctive career paths, so may secondary schools.

Good News

To conclude these comments on a positive note, here is just one among several success stories.

The state of Massachusetts has invested significant time and resources in overhauling its vocational education programs. The academic levels of its vocational high schools are now seen as on a par with those of its traditional high schools. In 2013, averages on the state English tests were essentially equal (92 and 93 percent), while the averages on the state math tests were close (78 and 82 percent). The graduation rate at its vocational schools was 95 percent versus 86 percent at its traditional high schools. The principal of the Minuteman Regional High School, a vocational school in Lexington, Mass., noted that its students get the same kind of college prep that they would get at any high school, and can study more than the traditional industrial trades, citing biotechnology and engineering programs as examples.

I welcome your feedback on this dynamic and often controversial topic.

Resources

- Daggett, W. R., Vocational and Industrial Education: Current Trends https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2533… Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- McCaslin, M. L., Vocational and Technical Education: Preparation of Teachers https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2534… Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Castro, C., Vocational and Technical Education: International Context https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2535… Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Gordon, H.R.D., Vocational and Technical Education: History of https://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/2536 Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Castro, C., and A.C. Andrade, “Supply and Demand Mismatches in Training: Can Anything Be Done?,” International Labor Review, 129 (3) 1990.

- Ravitch, D., Left Back: A Century of Failed School Reforms, Simon and Schuster, 2000.

- McCaslin, M. L., and D. Parks, ‘Teacher Education in Career and Technical Education: Background and Policy Implications for the New Millennium,” The National Dissemination Center for Career and Technical Education, 2002.

- Gordon, H.R.D., The History and Growth of Vocational Education in America, Allyn and Bacon, 1999.

- Scott, J.L., and M. Sarkees, Overuse of Vocational and Applied Technology Education, American Technical Publishers, 1996.

- Christiansen, D., “In Praise of a Job Well Done,” ieee-usa today’s engineer, Apr. 2011.

- Christiansen, D., “Making Stuff,” ieee-usa today’s engineer, Aug. 2011.

- Christiansen, D., “Make and Learn,” ieee-usa today’s engineer, Oct. 2014.

- Christiansen, D., “Math: What Good Is It?,” The Best of Backscatter, Vol. 5.

Donald Christiansen is the former editor and publisher of IEEE Spectrum and an independent publishing consultant. He is a Fellow of the IEEE. He can be reached at donchristiansen@ieee.org.